“Americans Love Golf as a Conquest, Scots Love Golf as a Game”

Whenever I am out and about amongst new folks or socializing in a group setting where people do not know me or anything about who I am or what I do, and the usual chit-chat starts getting bantered about, with the typical mundane questions about who you are, where do you live, etc.

The conversation will always veer to some variant of “What do you do for work?”

When I reply, “I Play Golf, ” the conversation immediately takes on a whole different vibe and direction.

Sometimes, they look skeptical, laugh, and repeat the question, “What do you really do?”

Others might say, “Oh, you are retired, or some other clever remark or comeback, as they then delve deeper and inquire, “What did you do before that?”

When the answer is still the same, the conversation begins the whole business and nonsense of explaining that I am a Golf Professional by trade, golf is my real job, has been for over fifty years, and I have been involved in the sport my whole life.

Then begins a detailed and tiresome process of amplifying and adding details to my almost half-century engagement and membership in the Professional Golfers Association of America as a PGA Master Professional, coupled with an endless variety and assortment of tasks I have performed along the way while playing the game of golf.

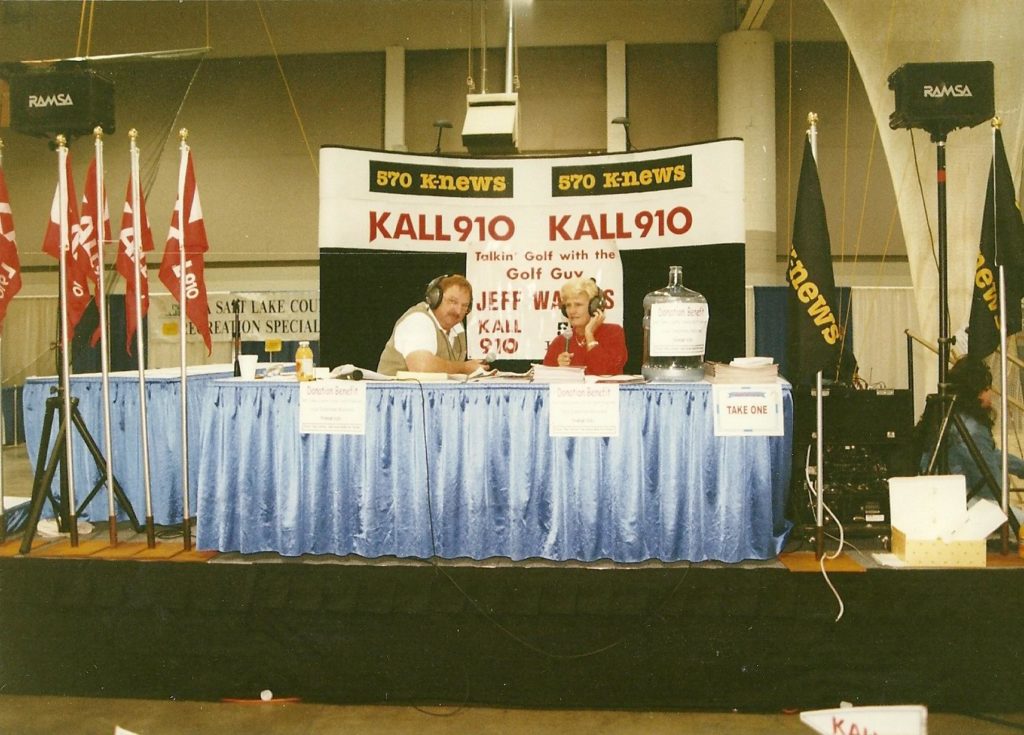

Additionally, I have been in the public arena as a Broadcast Journalist, Writer, and Talk Radio Host for almost forty years while airing a weekly two-hour syndicated golf show.

Employment that covers the whole gambit of my working career in the golf business.

After reciting my resume and career highlights, the dialogue might continue if the person is still interested, has yet to fall asleep, or has not walked away.

In that case, the conversation usually involves a rundown of the golf courses I have worked at, positions held, tournaments I have played in, Championships I have covered, and whether I know Tiger Woods, etc.

Invariably, if the exchange persists and lingers, it never fails; “What is your favorite golf course?”

That inquiry generates a whole new litany of responses and answers.

Because that is a question I cannot begin to answer.

It is akin to, who is your favorite child, preferred city, or most-beloved relative?

It is an impossible task to convey or consider because each of the hundreds of golf courses I have worked at, played, visited, or broadcasted from during my journey throughout my golfing life calls up a particular delight and appreciation of each of those individual locations, events, or tournaments.

Each one summons its own remarkable recollections, histories, and memories.

How do you choose?

I cannot, or the simple reason is that every golf course on earth, in my view, is a whimsical, fanciful, and genuinely memorable destination, a beautiful thing like a fine wine, a work of art, or a unique piece of music, regardless of where or when I might have encountered those properties or traveled to on this planet.

There is no place on earth I would rather be than on a golf course as the sun sets on the 19th hole and another blissful, perfect day, and I have spent much of my adult life recording and preserving those reflections as best I can, for each visit is distinctive, extraordinary, and incredibly special.

My passage into golf was foreordained and determined from an early age.

That emersion and foray into the lifestyle of Professional Golf that fated this engagement combined two separate yet cooperative historical accounts: the Mormon pioneer saga and Golf’s early history in the Western United States.

Each of these narratives embarks during the middle of the eighteenth century on the eve of golf’s first significant expansion into America’s consciousness and the Mormon’s enforced displacement into Utah Territory and unfolds with this venerated and celebrated account and portrayal.

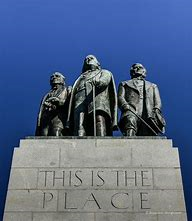

Three days before Brigham Young led the Mormon migration into the Great Salt Lake Basin on July 24, 1847, Erastus Snow and Orson Pratt entered the valley on an advanced reconnaissance exploration.

They turned left at the mouth of the Emigration Canyon, following the route Interstate 215 now occupies on the valley’s eastern side.

After circumventing and exploring the valley floor, those adventuring explorers returned to their entry point, below the opening of Emigration Canyon, high on the rocky foothills of the east bench, then trekked further south, setting their base camp at the mouth of Obit-ko-ke-che, ean’ka-so-kuup, The Goshute Indian Tribes’ name for Big Canyon, from which flowed a crystal clear creek, later giving the region its anglicized name and identity.

The area and stream of their discovery were renamed later for Parley P. Pratt, who settled the area and built the first road navigating the passage through the canyon, which evolved as the pioneer’s primary entry into the Vally and later developed as a major east-west thoroughfare across Middle America.

Those men realized then, and what history has since acknowledged to many people that select this valley as their home, the beauty, accessibility, and setting of the Parley’s Creek Corridor make this one of the most choice and inhabitable avenues in the Salt Lake Valley.

The abundance of arable land, vegetation, wildlife, vistas, and the essential element in a high mountain desert, an abundant water source, impressed those early Mormon scouts.

When he arrived two days later, the advance party encouraged the Mormon leader to settle in this part of the valley; nevertheless, when Brigham Young emerged from the canyon, he turned right and set up the main encampment for his intrepid band of pioneers farther north on the flatter land and banks of the more reliable-flowing stream of City Creek.

Whether owing to divine inspiration or the genius of a master colonizer, President Young saw, on that hot, steamy July day, the main encampment for those hardy trailblazers, now Utah’s capital city, lay on the northward end of the Salt Lake Valley, not the south.

However, that is not how this story concludes or the ending of those early pioneers’ encounters with the Salt Lake Valley’s distinctive topography.

Little did those early pioneers realize the ribbon of water flowing from the yawning portals of Parleys Canyon would provide a natural corridor that coursed through the heart of the Salt Lake Valley, used not only for traversing the wetlands and boggy marshes that carpeted the valley’s expansive countryside, but expanding the riparian interface, creating natural sandbars, ledges, fertile plains, and flatlands while depositing its rich loamy topsoil forming the landscape for the numerous settlements, farms, orchards, cities, and towns that would later be developed and scattered across in the Salt Lake Valley while framing the streams pathway on its inevitable advance towards the Great Salt Lake.

When Mormon pioneers fleeing religious persecution first entered the Salt Lake Valley, Utah, it was a vast, barren, high-mountain desert with few natural stream beds and flowing waterways; Parley’s Creek was one of those and bisected the middle of the Valley.

Indigenous tribes of Native Americans had left the area, leaving the hardscrabble newcomers to fend for themselves with little more than what they could carry on their backs; these early pilgrims arrived in the Great Salt Lake Basin, scrapping for food, shelter, and the necessities of life.

That soon changed.

Six months after Brigham Young led the historic Mormon exodus into the greater Salt Lake Valley and the winter snows had cleared, he sent his envoys throughout the region to explore and colonize potential settlements, with the directive “Go forth and prosper.”

When settlers got established and put down their roots, those hardy pioneers first built a church to worship, a cemetery to mourn, honor, and bury their dead, and a community park where the public could recreate and gather socially.

Golf was introduced to America in the early part of the 19th century, just fifty years after the imposed Mormon relocation, and gained popularity nationally with the likes of Bobby Jones, Gene Sarazen, and Walter Hagan and locally with Salt Lake native George Von Elm, bringing exposure to the sport; it was only natural for those early Mormon communities to add a golf course to their recreational and outdoor areas.

Those first courses were crude, elementary designs, hand-built, supported, financed, and operated by the local population, which in some measure explains all the quirky, idiosyncratic, modest nine-hole golf courses found throughout the State and why Utah has the highest percentage, of public golf courses, per capita, anywhere in America.

In 1894, the sport of golf took on a national identity when the United States Golf Association, formed with five original members, was organized to promote the game, develop rules, and foster competitions on a national scale.

With newfound stability and structure, the game of golf continued to grow, expand, and flourish.

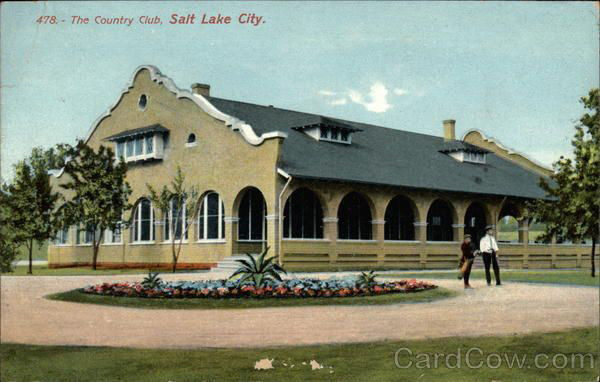

By 1910, there were 267 golf clubs in America, including Utah’s first golf course, The Salt Lake Country Club, located right smack dab on the banks of Parley’s Creek, and the golf course I grew up next to and learned to play upon.

An area and neighborhood that allowed me to submerse myself into the game of golf and a sport that launched me on the road to a life and career in a business that had flowed through my personality and ingrained itself in my presence from the beginning of my first exposure to the ancient Scottish pastime.

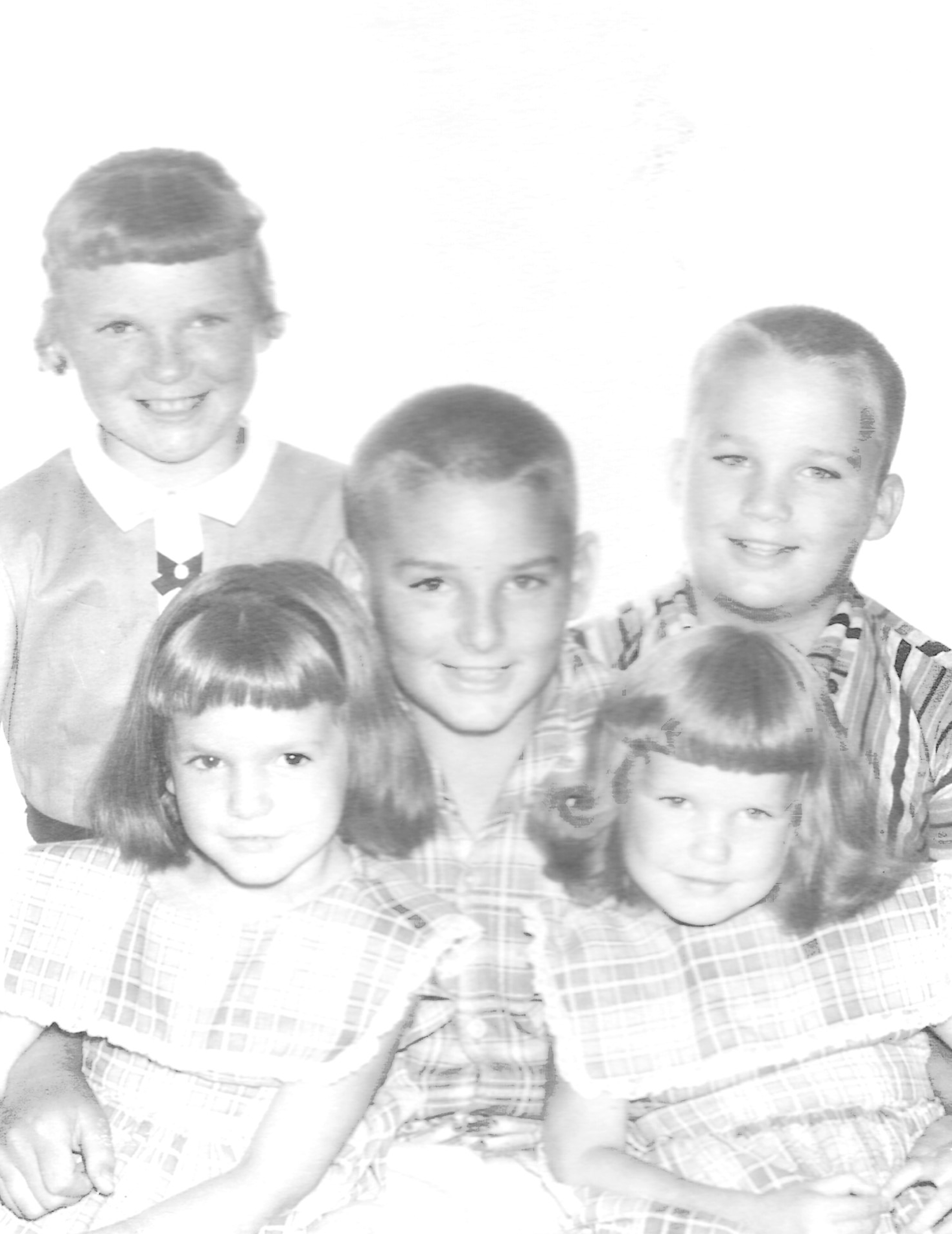

An active, curious child, I was blessed to be born and come of age in a middle-class environment with loving parents with few structural or economic disadvantages.

My family was neither well-off nor privileged, but I cannot remember wanting or needing much while growing up.

I was a happy, complacent youngster with boundless optimism and countless opportunities for enjoyment and diversion owing to my large family unit and our extended community.

My family were sixth-generation Mormons and direct descendants of pioneers who emigrated to Utah in 1847.

We lived in the Sugarhouse suburbs of Salt Lake City with all the related cultural and social benefits and communal advantages of a built-in convergence of similar and like-minded cohorts, friends, and neighbors.

Households and neighborhoods connected and intertwined with the ever-present and ubiquitous LDS meetinghouses, which populated all Utah communities and, in my immediate area, was situated directly across the street from where I was raised.

Places of worship with an attached culture hall and full-sized gymnasiums were always open, offering cost-free services while supplying year-round recreation possibilities, spiritual guidance, surrogate fostering, and an incomparable environment to grow, learn, play, and develop.

This wholesome, safe, and moral environment where I was raised was one city block, just three football fields away from what was once the private Salt Lake Country Club, now renamed and maintained for public use as Forest Dale Golf Course with its historic clubhouse left behind from its Country Club days, where I was raised, hung out, and came of age.

This oversized and sprawling property contained not just a golf course but a sizeable inner-city park filled with ponds, creeks, fields, and meadows for exploration and adventure, with an attendant swimming pool, tennis courts, ball fields, and picnic areas adjacent to a Boys and Girls Club, maintained by the YMCA, which offered unlimited amusement, hobbies, leisure, and social activities.

It was a magical place to grow up, a recreational wonderland that satisfied my every wish, need, whim, and desire.

In my Pollyannaish nativity, I believed every kid in the world grew up and got to experience the same idyllic upbringing and environments I took for granted every day of my youth.

Little did I realize that my childhood background and childhood were gilded and fortuitous.

Like most kids raised in Middle America during the post-war era of the 1950s and ’60s, the outdoors was the place to be and all it entailed.

Long before the electronic revolution deadened the senses of following generations, baby boomers, born mid-century as my age group was collectively called, had to create our playfields and make up our games.

Cops and Robbers, Cowboys and Indians, Pirates and Buccaneers.

Nightly raids on the neighbor’s gardens and orchards.

We were wading and swimming in the ponds and streams that inhabited our immediate area with no health concerns.

Climbing trees and playing in the woods and fields, we engaged in get-up-and-go like there was no tomorrow.

We had fun and enjoyed life, scrapping, tussling, roaming in the streets, growing up, hunting, fishing, and playing sports on the backlots, alleys, fields, and open spaces wherever the need or inclination arose.

We did it all with unrestricted playtime without parent intervention and then did it all again.

And why not?

We were invincible, strong, and never got tired or bored.

It was an era of boundless joy and harmony.

No one in my community locked their doors to their houses, nor were parents concerned about where or what you did if you were home before dark.

The neighborhood policed itself, including other kids on the block, if they warranted or deserved it.

Ours was the first group of American youth to survive a worldwide apocalypse, and as an entire generation, we had no clue how blessed and lucky we were.

Nor did we care or ponder the reasons why.

We lived for the moment, whether morning, noon, or night; tomorrow was another day with more fun and adventure.

Rough and tumble was the game’s name, and we were free-range children without overbearing and unnecessary supervision.

The older generation and those who had prevailed and survived the days of reckoning understood on a profoundly personal level how self-sacrificing, just, and admirable the world was to have escaped the worst aspects of human nature and behavior that could have affected the entire global population with catastrophic and disastrous results.

Our parents and their parents had endured two world wars and the most significant depression humans have ever seen.

Those who had survived the forgoing battles, our parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and all those who had done the heavy lifting, performed the heroic deeds, made the sacrifices, they knew how blessed and lucky our generation was to now live in a new age of peace, prosperity, and tranquility.

My generation grew up with this mindset, and our parents’ reluctance to impose limits on their kids prompted baby boomers to become the most permissive, selfish, indulgent, and entitled age bracket humanity has ever seen.

Sex, drugs, and rock and roll became our mantra and were a universal anthem amongst our peer group.

Our entire age bracket identified with the movement’s philosophy even if you did not join in physically.

It was a time of great turmoil and introspection for a tattered and tired group of older Americans now looking for an improved and more peaceful lifestyle for themselves, their offspring, and their families, and why our parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles became contemporary history’s most accommodating, lenient, and tolerant mentors and guardians the world as ever known.

You were part of it and wistfully embraced it, if only in your most secret dreams and fantasies.

I mean, seriously, who did not wish they had attended Woodstock?

Grow their hair out, surf the beach, fall in love, and dance the night away without a care in the world?

We partook of all the forbidden fruits and selfish pleasures that society offered, as did most of the people I grew up with, associated with, and knew socially.

We all participated in some form or another.

It was a lifestyle we thought would never end, and we lamented grievously when it did.

An existence and mentality that persisted throughout life and inflicted profound consequences and outcomes that endured into parenthood and middle age that influenced and changed how we, as an entire generation, perceived the world, raised our children, and interacted with society.

Amidst this awakening and social reckoning, I grew up marching to a slightly different tune and circumstances.

I was a nerdy, curious jock and not much for television, work, or girls as I matured and started to develop physically and emotionally.

Books, sports, and the outdoors occupied all my waking hours.

Football, baseball, and basketball, each in their season, with a bit of golf thrown in to fill the gaps; if I was not playing or practicing sports, I was reading, which I continue to do.

My favorite day of the week in summer was always Mondays, when the bookmobile from the public library stopped on my block across from the house, and I could replenish my weekly allotment of new stories to check out.

I devoured the latest volume cover-to-cover during those quiet, peaceful, undisturbed waking hours when I was not involved in some form of outdoor amusement or competitive sports.

I continued this pattern throughout my public school education, a ritualistic exercise of stopping at the library each morning, selecting a new book, reading it throughout the day, and returning it after school.

A practice I carried out throughout my entire Middle and High School years.

I was a bright, curious student, and school came easy except for math, which came back to haunt me when I entered graduate school and had to take remedial algebra to complete my statistics and marketing courses.

I read fast, retained comprehension, recalled obscure facts, figures, and minutiae, and took a good test.

I also had the beastly habit of marking my place in each new volume by bending the top right corner of the last page I had finished at a forty-five-degree angle to remind me of my spot and if I had read the book by checking the pages for creases.

I am confident that I perused and marked most of the books in my school’s libraries by the time I graduated.

My interests run the gamut of popular fiction, human interest stories, biographies, and history; curiously, I needed more inclination when pursuing romantic, science fiction, or fantasy literature.

At an early age, however, I became enthralled with “New Journalism” and writers who researched their subject diligently, scripted it intensely, and immersed themselves in their dialogue.

My reading involvement began with young adult works on adventure, sports, and history but soon progressed into the contemporary classics, including Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson, Earnest Hemmingway, Arthur Conan Doyle, Jack London, James Michener, John Steinbeck, Virginal Woolf, Leon Uris, Herman Wouk, Joseph Conrad, and Scott Fitzgerald.

I tried to read them all.

As my tastes evolved, I moved into the world of Gonzo, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Hunter Thompson, P.J O’Rorke, and Gay Talese.

I enjoyed literature that let the writer enter the story with their opinions, ideas, and personal involvement and take me along.

Naturally, being a sports and golf guy, I was enthralled and soon immersed myself in the commentaries and prose of Benard Darwin, Grantland Rice, Jim Murray, Furman Bisher, Dan Jenkins, Henry Longhurst, and Herbert Warren Wind, all preeminent sports journalists, and except for Darwin and Rice, I fortunate to know and later worked with each of these esteemed writers in pressrooms, golf tournaments, and sporting events around the world.

What I learned from each of those authors’ examples was that they used the playing fields of sport as metaphors for life’s lessons while emphasizing and characterizing the absolute absurdity of the games, the athletes who played them, the oversized privilege and excess ego of the participants who collectively share considerable confidence in their talent and abilities born of inherited genetics, and the out-and-out humor and amusement through it all.

It was a thrilling and exciting atmosphere to roam about and associate in.

It was easy to embrace as a philosophy as I became a PGA Golf Professional, Writer, and Broadcast Journalist.

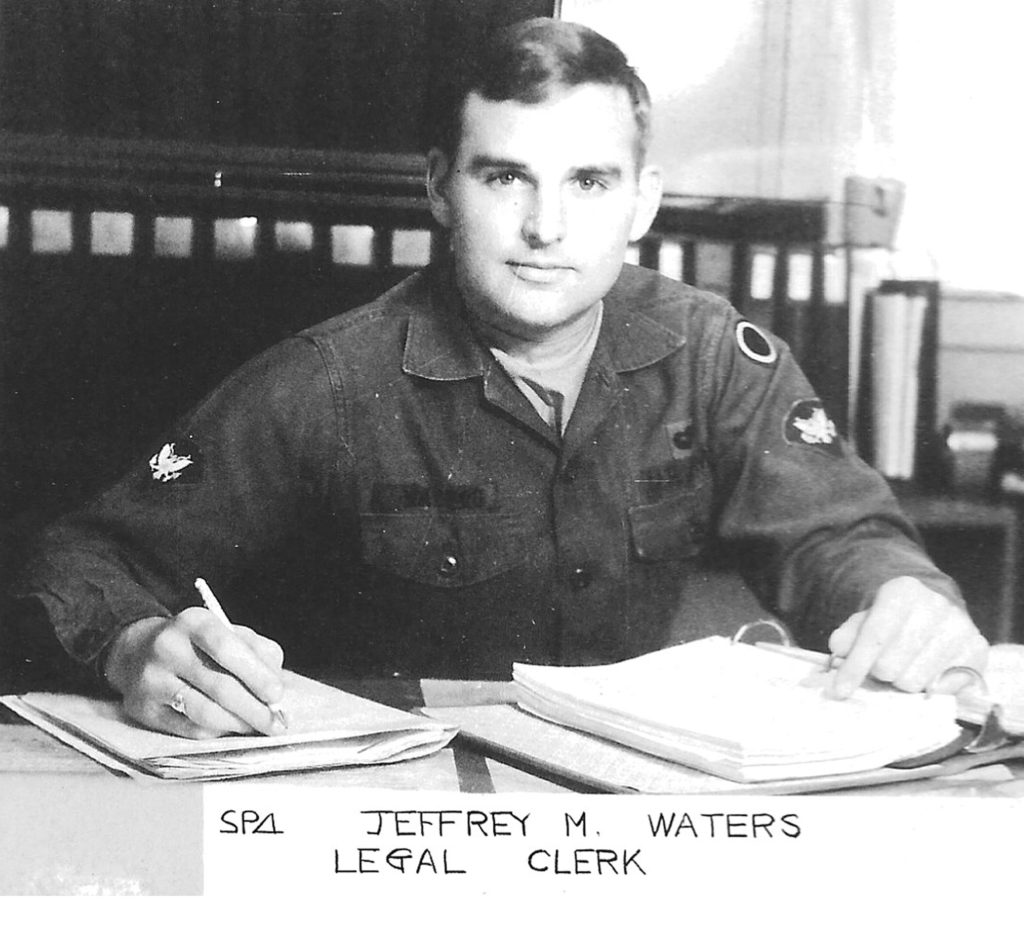

I began my journey considering the possibilities of a future in the golf business when I returned home to Utah following an overseas deployment in the United States Army.

My path in life before my epiphany pursuing a golf lifestyle was a caricature of conflicts: physical, intellectual, moral, and emotional.

In my quarter of a century of existence, after a succession of varied and diverse involvements and experiences, I had yet to understand where I was going or how to get there; my life was a muddle of desires, wants, and aspirations.

I was still determining what I wanted to do or what I wanted to be.

I needed direction, vision, and forethought to prepare for the rest of my life’s ups and downs, which, in my youthful exuberance, I thought I had acquired.

I realized that all past experiences and encounters needed to be more robust in substance, and it took a while to cultivate and understand.

Life was carefree and straightforward when I graduated high school, and the direction was specific.

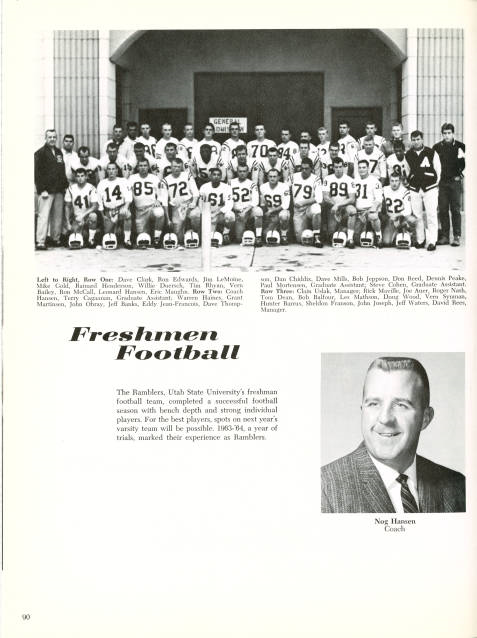

I would be attending Utah State University in Logan, Utah.

I was on a scholarship and wanted to see if I could play football at the next level.

The University allowed me that opportunity and the bonus of leaving home and venturing independently.

Both experiences were dreadful mistakes and hugely unsuccessful.

Football was fun for a while, but I quickly realized that with my lack of talent and lingering injuries from high school, I would never play in the NFL, and the exercise soon became tedious and just another chore.

Living away from home in the dorms is mandatory for incoming first-year students with its attendant rules, procedures, and protocols.

It was too much work and confining for my disposition and temperament.

Coupled with the casual indifference of so many students from differing cultures, backgrounds, and ethnicities to abide by and adhere to communal norms, conduct, and polite and mindful manners, the environment required restraint and self-discipline, which was difficult.

I am not racist, a prude, or homophobic, but there was so much noise, clamor, turmoil, and far too many people all living in the same place, creating a cacophony of annoyance and commotion.

So, I pledged to a fraternity to escape the forced residency constraints of living with other students.

I then moved into the chapter house on fraternity row, satisfying the university’s requirement to live on campus.

Which only marginally raised the quantity and quality of my new housemate’s life experiences, behaviors, and imaginary level of sophistication, with the presumed privilege each claimed as their right, combined with the endless parties and mindless chatter that surrounded the diminished size of the populace I was now compelled to live and socialize with.

So, I quit, dropped out of school before they kicked me out, went back home with my tail between my legs, explained and apologized to my disappointed parents that I was not cut out for college life or living with other people, and got a job, which seemed the next step in the evolutionary process.

Growing up, I had many assorted and odd jobs working part-time as a part-time paper carrier, dishwasher, server’s assistant, and baker’s assistant in the service industry.

Nothing serious piqued my interest or career expectations.

My first real job out of high school, expecting to play football in college, was working in manufacturing and construction and loathing everything about it.

From the early morning wakeups, the grime and drudgery, the sheer labor-intensive physicality, and packing a lunch bucket every day.

Most of all, I saw and felt my fellow workers’ discontent and unhappiness about their predicament and lack of a foreseeable future.

I vowed then that was not the life I would choose.

I needed to be happy; most of all, life had to be enjoyable.

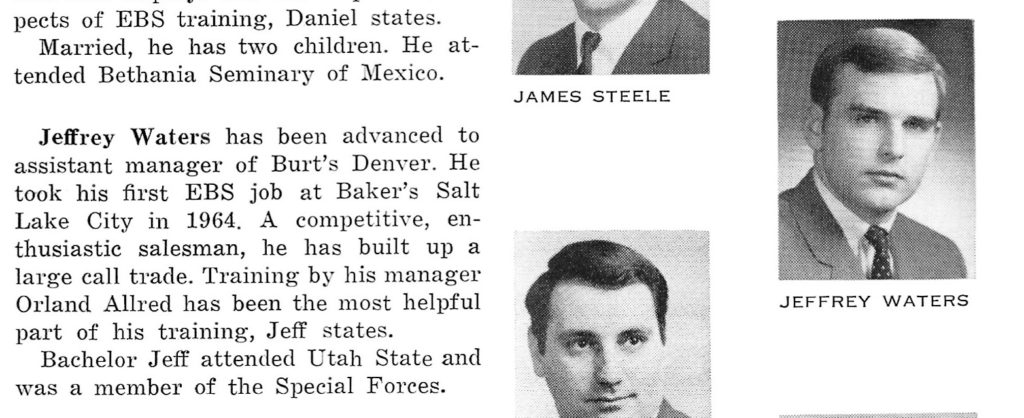

After my brief foray into college and returning home to the safety and privacy of my parent’s home and my old, comfortable bedroom, I went to work in retail sales, peddling women’s shoes in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah, and discovered I enjoyed it immensely.

I embraced the lifestyle, standard of living, the hustle and bustle of big city employment, and the everyday delight of meeting and interacting with new, different, and exciting people, using my wits, wearing nice clothes, and working a flexible schedule with time off for lunch and late-night dinners.

Plus, I was making good money, learning a craft, enjoying living, and having fun.

The city center business culture of the mid-sixties has heady stuff for a wannabe man-about-the-town putting on airs and spreading his nascent wings trying to soar above the day-to-day and crowded playing fields of unadventurous and indifferent, staid, predictable, baby boomer adolescents pushing, and shoving their way to sameness below.

However, this serendipitous and satisfactory lifestyle I was enjoying, moving smoothly forward amidst the flowers, love, and sexual freedom of the Beat Generation in undisturbed and peaceful contentment, could not last and, regrettably, did not.

The world, as I and the rest of those living in those giddy and intoxicating times soon realized, the proverbial rug could be pulled out from beneath us at any moment, and the sparkle of this beguiling existence could shift in a heartbeat.

And it did.

The realization of impending reckoning was first unmasked when the United States, to its everlasting folly and regret, waged battle and destruction against a small, impoverished Indo-China nation for dubious reasons that altered the trajectory, hopes, dreams, and aspirations of an entire generation of young men entering the best part of their lives.

America was now in a State of War, and being of prime age, the United States Government requested my attendance, and I responded.

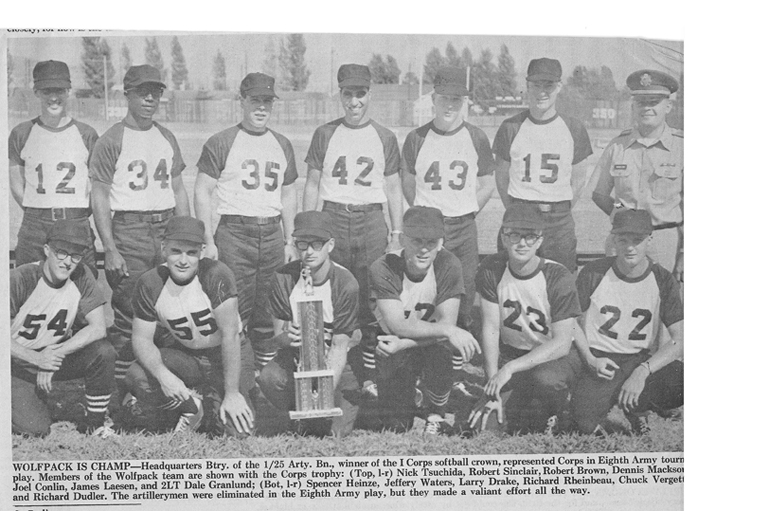

A product and offspring of the Greatest Generation and the ingrained pride of country and flag that cohort instilled in their progeny, I replied to my Nation’s call of duty by joining the Utah National Guard and enlisting in the United States Army’s 19th Special Forces.

I was justifiably proud of my military service, including the rigorous and specialized training I endured during those turbulent years of the Vietnam conflict.

I took pride in serving, becoming a celebrated Special Forces member, achieving Airborne Qualification, and wearing the coveted Green Beret.

For the next five years, during those turbulent and malevolent times, I juggled my job responsibilities, full and part-time military service, career moves, and the ups and downs of conventional life as I sought higher and meaningful purpose amongst the rapid social upheavals of a polarized and conflicted world that was rapidly transforming and revolutionizing the very fabric of its and my existence.

The entire era of the sixties was a strange and chaotic time.

Civil Rights, Voting Rights, Gay Rights, Women’s Rights, the Counterculture Movement, The Sexual Revolution, and a noted uptick in environmental concerns.

I tried my best to live and function in an expected, conventional, mainstream reality.

I climbed the corporate ladder, succeeded, was promoted to management, and transferred to Denver, Colorado, in 1967.

Seeking some decorum and responsibility, I settled into a mundane, unremarkable, everyday life and envisioned establishing deeper roots, getting married, and investing in a home and business.

It seemed as if fortune and my home-schooled values now influenced and governed my every practice, and I was caught up in the ethos of the time, where my future was predictably ordained, defined, and established.

After years of contradiction, I was settling down and following the blueprint my parents had installed in my character.

Then, in 1968, the world I knew and was beginning to enjoy and appreciate was turned upside down.

I had achieved some measure of success in the culture and social order during those peaceful, laid-back Summer of Love Days and had settled into a predictable routine that quickly collapsed at the seams.

In a few short months, the brutal murder of progressive icons Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King shook society’s foundation.

On the war front, the Tet Offensive in Vietnam shocked the military-industrial complex, forever changing the American Public’s belief in a conflict being fought at significant personal and economic cost, far from American shores.

Nationally, anti-war riots broke out in Chicago and other large cities, and Middle-Class America was shocked at the violence the Peace and Love Generation perpetrated against established authority and rule.

This forceful and enthusiastic behavior ended the years of possibility, promise, and optimism that began with a man on the moon, ended with days of rage, and abandoned the illusion of the pleasure-seeking, self-absorbed cohort that defined the complexities and lowest point of the sixties.

Finally, the defining action of this era severely tarnished the baby-boomer generation, ending the years of hope for a kinder, gentler America and sealing my fate and that of many of my contemporaries.

North Korea had blatantly seized the American naval vessel US Pueblo, capturing eighty-three crew members aboard, intensifying the disagreement and State of War between The United States and North Korea.

North Korea’s military aggression escalated the ongoing struggle between the two long-time adversaries, altering the national military posture, forgoing all graduate school deferments, and ending college exemptions from the draft, precipitating the calling up of military reserves and extending their terms of military service.

Including yours truly.

Three weeks later, after rapidly buttoning up all my pressing commitments and obligations, including saying goodbye to my fiancé and long-time girlfriend whom I would never see again, leaving my burgeoning, middle-class lifestyle, work, and living arrangements, which I could never return to, I reported to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and the overseas replacement station awaiting immediate transport to the Republic of South Korea, and a War Zone I thought I would never grasp, see, nor participate in.

Dazed, and shortly after arriving in Pusan on the southern tip of the peninsula, I was headed north, traveling above the 38th parallel towards the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Korea, where I would spend the next thirteen months, twenty-three days, carrying a loaded weapon, collecting hazardous duty pay, contemplating my future, or lack of, and wondering how in the world my life, lofty expectations, and prospects could be transformed so quickly, with such devasting consequences, and how this could have happened to me?

The only enduring thought about my present dilemma and its long, lonely nights was that I had a year to contemplate my situation with its predictable dreariness and monotony because I had nowhere to go and plenty of time to think about it and plans for my future.

By some perverse logic, as I deliberated my predicament, the recurring thought that ran through my subconscious mind was that, somehow, I had gotten a makeover.

I had been saved from a probable, conventional, and banal life I had been fast-tracked for.

I now had a clean slate that had wiped out all my yesterdays, the history, accounts, and relationships of times gone by, good and bad. From now on, I could control, shape, and mold my destiny, whatever it might be, as I saw fit.

The only dilemma was I had to get out of Korea sane and in one piece.

It was cold, bitter cold, and the biting chill of the frozen night seeped through every layer of my winter gear.

The crunch of trampled snow beneath my boots was the only sound disturbing the stillness of the star-filled night.

The brightness of the searchlights rising above the lookout posts every hundred yards cast eerie halos outside the double rows of concertina wire safeguarding the camp’s perimeter while extending their flickering glow beyond the inky blackness that stretched endlessly into the shadows of the barren and battle-scarred countryside.

I was on guard duty, walking the fence line with a half-hearted conscientiousness and bone-chilling weariness.

The task’s uneasiness promoted a menacing tenseness that intensified as the night progressed.

My thoughts ran unchecked and swelled with wakefulness, only dampened by the routine and sameness of each passing hour.

My nose wrinkled and clogged from the stench of the cooking fires that wafted and hung heavy from the nearby Ville while the pall of the smoke they fashioned lent a hazy layer to the night sky.

Despite the frigid temperature, my probing eyes never left the fence line, trusting the tramped and worn pathway through the snow leveled by scores of sentries who trooped this track before me.

Unease was a constant companion as I searched and surveyed the landscape outside the wire, seeking demons and phantoms lying in wait and prowling beyond my night vision.

Worry, dread, and nervousness of the unknown and unseen cripple your soul and constrain your inner self, more profound than the icy blasts ripping through your winter hood and helmet.

They were out there, watching and waiting; you could feel their presence with each step you took, and suspicions grew more prominent with every image imagined lurking in the shadows, summoned in your mind, flashing continually through your consciousness.

With fright and foreboding, those thoughts and fantasies gathered and amplified.

The camp was in the war zone, just a few short miles south of the DMZ, and danger was always present, with North Korean soldiers gathered along the border that separated the two countries.

Infiltrators, spies, and undercover agents were continually slipping through our forward lines to observe and probe our defenses, watching me as I searched for them.

Apprehension and fear are unnerving motivators when hopelessness and despair plummet into the unashamed depths of melancholy.

A state of mind that can only be mitigated with thoughts of better days, hope, belief, and expectations that my future outlook and prospects for a better tomorrow will improve.

Walking the guard line, with its long hours of never-ending contemplation and deliberation, afforded me ample time to think and ponder alternate viewpoints. This amended my outlook and perception of what I needed to do to be happy, optimistic, and successful when I entered civilian life again.

The army will do that to a person.

With its vertical chain of command, differing levels of authority, and strict hierarchal system, the military stifles originality while rewarding a divine sense of entitlement with its rigid system of rank and privilege.

But not just the army, with its entrenched and structured culture, made me think and envision my plight.

The military revealed me to a line of reasoning that changed my mindset and attitude, which had slowly ripened throughout my youthful, unsophisticated years of assorted and diverse encounters, which had lacked organization and development and had, up until now, been easy and carefree.

I had gotten by on good fortune, luck, cleverness, some degree of talent, and a generous measure of pluck, brashness, and bluster.

It was time to change direction, get off guard duty, and do something with my military career.

What I recalled from all my past involvements and the emotional and physical trials and baggage they presented, and the army had reinforced this throughout my year-long tour, is that a good number of people who receive praise from their professed importance or privilege and then coupled with inadequate know-how, training, or education, thrust into positions of authority for whatever reasons and then promoted upward within those structured hierarchical systems, gaining positions of power while collecting measures of accomplishment from that upward mobility, are inclined to overestimate their self-importance and vanity.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the military.

This entitlement, when coupled with a stubborn self-denial of the many opportunities, advantages, or support that boosted them to their achievements, habitually empowers them to mistaken claims that, rather than some quirk of fate or happenstance, it is their singular self-fortitude, grit, determination, talent, and the proverbial “pulling themselves up by their bootstraps,” that allowed them to achieve their access to good fortune and special privileges.

This arrogance and self-delusion seemingly justify people in positions of power, their narcissism, lack of humility, and empathy towards individuals afforded lesser opportunities.

An attitude and way of behaving, after my year in the army, I now loathed, despised, and vowed never to embrace.

That was the recurring theme as I reflected on my previous experiences and contended with The Good Old Boy Network and the social and community inequality those involvements infiltrated and permeated my present and past.

And I promised myself again, with each frozen footstep I took, that if I made it out of Korea alive, my life would change; I would be more tolerant and easy-going, and I would return to college with a renewed commitment and compassion, using my talent and consideration for my fellow man, along with a recharged purpose for whatever road lay ahead.

I knew without a doubt that education would be the key to whatever success I might find in the future.

In the present, I soon realized my only recourse and relief from guard duty, enforced bureaucracy, and all the mundane dreary jobs associated with military life was to move into administration using my intellect and education and obtaining the legal clerk position for the entire Battalion while adjudicating the legal affairs for the two thousand members of my organization, and participating in sports, so for the rest of my tour, I did both, played football and baseball on battalion teams, traveling the length of the country performing and barnstorming on the playing fields and ball diamonds all over South Korea, while retaining my sanity and a sense of purpose.

The Seattle-Tacoma International Airport was a beehive of bustle and activity, jammed with passengers, visitors, and returning servicemembers arriving home from the Pacific Theater.

The main demarcation and separation depository for all military personnel inward bound from Southeast Asia, Japan, and Korea was teeming with commotion and hubbub, coupled with the unavoidable din and clamor arising from the chorus of demonstrators and protestors amassed outside the central terminal.

The bus from Fort Lewis had dropped me and the other newly discharged GIs off at the main entrance, but we were now alone and on our own as we disembarked and braved the gauntlet of anger, spite, and hatred that accosted our arrival.

We had heard the stories and watched news coverage of the welcoming committees that would greet our appearance and return home from hostilities but were all taken back by the mob’s wrath and scorn as security kept a watchful eye.

Who, after years of war, enduring countless protests, and shepherding thousands of returning soldiers through the doorways of the building, were immune to the shouting, agitation, and discontent of the enraged hordes.

Security officers ignored the picketers, who were sequestered behind barriers preventing physical encroachment with the returnees, as we, with eyes adverted, hastily entered the building and scurried to our boarding locations and the safety of the loading gates.

As my flight finally became airborne, I sat back, took a deep and thankful breath, and watched the teeming Seattle metropolis disappear beneath the aircraft’s wings as the airplane gained altitude, circled out and over a placid and serene Pacific Ocean, banked, turned, and headed for Salt Lake City, and the home I had not seen for almost five long, meaningless, and difficult years.

My long psychological and emotional nightmarish ordeal was finally over.

I could now start anew, refreshed, and with a newborn perspective. I faced an uncertain future and an unaccustomed life, and I had no idea where either one might lead me.

There was no answer when I called my parents at home from the airport, which was unsurprising for two reasons: first, they did not know when to expect me, and second, it was a long Fourth of July weekend, and I knew they would be busy and out of town.

So, I took a cab.

The house looked the same, with the key in its usual place under the doormat.

I let myself in, went downstairs to my old bedroom, found some old clothes in the closet, and changed out of my uniform, which I hung carefully, ensuring my medals and awards were displayed prominently.

I went back upstairs and laid my dress greens out on the couch where they would be seen the first thing, laid down, and promptly fell asleep.

When I awoke, it was late afternoon, and the house was eerily quiet as I went back to check for changes in the yard and deck.

Waves of nostalgia and memories washed over me as I sat under the patio and reminisced on events and celebrations of the only house I had ever lived and grown up in and, for the second time in my adult life, a home I thought I would never return to.

It was getting dark, and with nothing to do and nowhere to go, I walked to the store, bought a twelve-pack of beer, returned home, and with newfound independence, I drank until I passed out.

Morning came early, and the house was dark and unresponsive as I stumbled groggily to the bathroom in the early daybreak.

I needed nourishment; as expected, they were both readily accessible, plentiful, and more than enough to appease my emptiness and headache.

Back in the family room, I slowly nursed my coffee, munched on a piece of toast, and little by little contemplated my uniform, still displayed neatly on the couch where I had left it on display and just the day before had worn proudly home in great expectancy and anticipation of my homecoming and reuniting with my family.

The more I studied it, the more it came across as vulgar, garish, and unbecoming.

I soon grew weary and bored of its grainy coarseness, old-school, and unfashionable attire.

So, I packed it up, carried it back downstairs to my bedroom, stashed it away in my closet, and never took it out nor wore it again.

Realizing my parents were not coming home anytime soon and it was a long holiday weekend, I called some old high school friends and asked if they wanted to party.

As I waited for them to pick me up, I checked the time on my wristwatch with its camouflage band I had purchased from the military commissary in Japan and worn throughout my year-long tour in Korea.

In a concluding act of defiance, closure, and a final symbol of my new freedom, I walked to the garbage cans at the end of the driveway and tossed away the watch, never wearing one again, as time now became my most important commodity and mine alone to keep.

I waited for my friends to arrive, and, for the second consecutive night, I partied into the wee hours of the morning, safely ensconced in my parent’s home, comfortably secluded in Utah, and shielded from harm’s way with nothing but time and thoughts of my impending future.

My parents finally arrived Tuesday afternoon, and, as suspected, they had spent the long holiday weekend at the family cabin in the mountains above Park City, Utah.

They gently admonished me for not letting them know when I would be arriving, but I explained that when the army said to go, I did not argue; I went.

We talked long into the night about the past five years, my many experiences, the serendipitous and circular journey I had taken to the present moment, and my plans for the future.

I also presented my proposal and a rough idea of my aspirations, which were both singular and straightforward.

Finishing my education was the key, training was the validation, and everything else was secondary. With it, self-determination meant freedom to plot my course.

With all my siblings married and gone, the house was conveniently empty.

If they permitted, I would get a job, return to college, and move back home until I could re-adapt to conventional life and begin to attend school regularly.

As a family member staying in their home, I would no longer be on scholarship; I would pay for board and room, help with the house and yard chores, respect their space, and abide by their house rules.

I was extremely blessed and fortunate that my parents were caring, open-minded, and trusting folks whose love was unconditional, who were never reluctant to send me off on another adventure, and whose home was always open and welcoming when I returned, no matter the circumstances.

They agreed with little or no stipulations and conditions other than to work hard at school, honor their house rules, and with a place to live and hang my hat, which is precisely what transpired, and in rapid order, four things happened.

First, I applied for the GI Bill to receive tuition compensation and get paid to go to school.

Second, I registered at the Veterans Hospital to be eligible for health care and medications.

Third, I completed the paperwork for admission to the University of Utah, transferred my credits from Utah State, was tested, and enrolled as a non-traditional student in the class of 1975.

Finally, with nowhere to go and nothing to do, and with school still months away, a friend asked me to play golf, and I soon became a fixture at the golf course.

The Pro, whom I had known for years, suggested, “If I was going to be there every day, I might as well go to work,” which I did.

Those two pursuits, Education and Golf, would govern my existence for the next half-century.

College would fulfill my intellectual curiosity, needs, wants, and the wonder and enjoyment of learning.

Golf would provide support and economic advancement while satisfying my physical compulsions, cravings, and competitive desires while affording me resolve and a reason to get up every morning.

This is precisely what happened for the next fifty years, and my everyday existence became a predictable lifestyle.

I studied and attended school in the winter and played golf in the summer.

Like clockwork, as the seasons changed, so did I, moving from one lifestyle and character to another, typically coinciding with the advent of Daylight Savings Time.

Along the way, I gained my diplomas, degrees, certificates, and accreditations while teaching, writing, and publishing at every level, including Middle School, High School, Community College, and University.

Active in Golf, I played competitively as an Amateur and Professionally, locally, nationally, and internationally; I joined the PGA of America, earned my Class A and Master Professional Classifications, and became a Head Golf Professional, Administrator, and Small Business Owner while traveling the globe promoting golf.

I also joined the Broadcast Media Realm by launching a syndicated talk radio show covering golf-related subjects, including attending and airing the Major Championships on the PGA’s annual schedule.

Meanwhile, fulfilling a long-time desire and compulsion to record my many experiences and encounters in the sport, I started composing and submitting articles, stories, and essays to various magazines, journals, and additional internet platforms and was accepted into the Golf Writers Association of America.

As an accredited Journalist and Broadcaster, I now embarked on covering and announcing Major Golf Tournaments worldwide while visiting, competing, and reporting from some of the most acclaimed and famous golf courses in the world, including those on every Continent and Country on Earth except Australia, China, Russia, and Antarctica.

Along the way, I got to play most of the Golf Courses on Golf Digest’s Top 100 list, including such iconic courses as Pebble Beach, Augusta National, The Old Course at St. Andrews, Valderrama, Portmarnock, and Shinnecock Hills.

At the beginning of this story, you asked, “What is your favorite golf course?

I had no answer because they were all fantastic venues.

However, out of all the courses I have been fortunate to visit, I remember most vividly those I did not get to play.

Even though I had booked a tee time, had people to play with, and was in the area with my golf clubs, I could not participate for assorted reasons and circumstances, to my everlasting regret and disappointment.

Each of those instances portrays its own unique, beguiling account and narrative.

So, here are three of the most celebrated, notable, and distinguished courses I’ve got to see and are: “The Best Golf Courses I Never Got to Play.”

PASTATEMPO GOLF COURSE-Santa Cruse, California, rated No. 37 in the World and No. 2 in California, Designed by Alister Mackenzie in 1912.

We were on the road to Reno and blew right through Wendover, Nevada, which is usually a compulsory stop for adventure and pleasure-starved boys from Utah.

However, later that afternoon, we were due in what is touted as “The Biggest Little City in the World” and needed to check in at the hotel, which was picking up the tab for our night’s stay.

I was on assignment for Kall 910 and The Intermountain Broadcasting Network, the radio station where I served as Director of Golf.

There was work to do, along with the obligatory glad-handing and chit-chat accompanying such nonsense.

We met the staff, had dinner, and interviewed management, the owners of the new golf course being developed just outside of town, and other notables from the local sports community.

This was a big deal for the area, highlighting the first significant construction of a major golf resort within the Reno City limits in decades.

The station was giving it major play, including broadcasting my regionally syndicated radio show. the following morning, from the hotel property before moving on to the Monterey Peninsula and the Open Championship being conducted at Pebble Beach Golf Links.

This was the first stop on a ten-day promotional junket billed as “The Road to the Open.”

We were covering the 2020 United States Open Golf Championship, which Tiger Woods eventually won in record-breaking fashion, at twelve under par.

This would be only the eighth time the US Open was contested in Southern California.

All the major sponsors were on board for the multi-day project, including picking up all the expenses and providing a new Toyota Land Cruser with all the bells and whistles for my crew, consisting of myself, another reporter, a photojournalist, and my sales manager, who attended to the trip’s logistics.

We all had press credentials and would be housed in the media hotel off Fisherman Wharf on the seventeen-mile drive entrance to the Monterey Bay area of Central California with its scenic coastline, beaches, marine life, natural beauty, and rich history, including some of the most well-known golf courses in the region.

The plan was to cover the Open, file my updates and reports, write up a story and blog post including pictures for Rocky Mountain Golfer, a magazine I owned and published, and enjoy unfettered access to one of the most significant sporting spectaculars in the world.

On Monday, we would cap off the venture by driving up the coast to Santa Cruse, where we had tee times, and checking off a marvelous inland links course that had long been on my bucket list by visiting and playing Pasatiempo Golf Course.

It was a celebrated and famous course that impressed Bobby Jones so much when he first saw it during the 1929 United States Amateur contested at Pebble Beach that he engaged its architect and creator, Allister McKenzie, to construct the Augusta National Golf Club in Augusta, Georgia, the eventual home of the Masters.

I was excited and looking forward to playing a course about which I had heard so much.

It was shaping into a perfect adventure, and everything was going as planned until providence reared its auspicious head.

On Mondays at Major Tournaments, media members may enter a lottery to play the host golf course.

The course setup has the same championship tees and hole locations the competitors play on the last day of the tournament.

Not for the faint of heart, it is a captivating way to test amateur games against the pros under exacting tournament conditions.

As luck would have it, one of my crew drew out and was selected to play Pebble on Monday.

This meant the rest of the group was stuck overnight in Monterey, and playing Pasatiempo became a wishful fantasy.

However, in my wildest dreams, I would never refuse a friend and fellow journalist the chance to play one of the most acclaimed Golf Courses in the world, especially with the USGA picking up the tab instead of the $500 Green Fee Pebble Beach was charging at the time.

It turned out to be an incredible opportunity for everyone.

My friend got to play at the world-famous Pebble Beach Golf Links, and we all spent another night and day unwinding at one of the most renowned destination resorts in the Western United States.

As our plans changed, I asked a fellow writer to join us the next day to complete the foursome.

I had reservations at the Historic Del Monte Golf Course, the oldest continuously operating golf course west of the Mississippi River.

Built-in 1896, Del Monte was the first golf course constructed on the Monterey Peninsula and launched the golf boom in Central California.

It was an absolute pleasure to play, and afterward, we all retired to the legendary Nineteenth-Hole Tap Room in the majestic Pebble Beach Lodge just off the picturesque eighteenth hole to wait for our friend, gaze in wonder at the pictures and memorabilia that adorn the walls, tell tall stories, and revel in the glories of another perfect day relaxing and gazing out at the Pacific Ocean and onto one the most well-known and recognized finishing holes in all of golf.

Afterward, when we were done, tired but exhilarated with the week’s proceedings, we loaded up the Land Cruser.

We headed out, leaving the California Coast and the excitement of the US Open behind.

We returned to Salt Lake City, completing a perfect excursion mingling amongst the prominent and celebrated Golf’s influential elites and high rollers.

It was an outstanding trip, and once again, we bypassed Wendover, never thinking to stop, wholly satiated and satisfied by our unique and wonderful adventure.

Like Pasatiempo, Wendover would have to hang on and remain on a future bucket list, awaiting another day and another venture.

NATIONAL GOLF LINKS OF AMERICA-Southampton-New York, New York, rated No. 5 in the world and No. 2 in New York, was designed by Blair MacDonald in 1908.

Over my thirty-five years as a journalist and radio host, I have attended and broadcasted over a hundred Major Golf Tournaments, most of which were contested at classic and unforgettable masterpieces from around the country.

Nonetheless, some novelty and sparkle had worn off with five Championships a year, including the semi-annual Ryder and Presidents Cups.

I now treated and managed them as assignments, which they were, and whose attendance and travel routines were predictable and etched in stone.

Although some duties were more noteworthy than others, including the Masters, whose annual trip to Augusta, Georgia, each April became a traditional spring rite, and any time a Championship was contested West of the Mississippi, especially on the West Coast, was equally as unique and remarkable.

However, New York State, principally the vibe and atmosphere of the location, has always been my favorite place to visit and broadcast from.

The upstate industrial district which includes the rural farmland scenery of the Finger Lakes wine country, the Erie Canal, Buffalo, Albany, Niagara Falls, the stately Catskill Mountains with their unique geographic diversity, and, of course, Long Island, with its quaint fishing villages and ultra-sleek living style, fantastic beaches and recreational sites have always caught my fancy.

I love everything about New York and its setting, including The Big Apple, the city’s inhabitants, their passion, the town’s hustle and bustle, and the cacophony of sights and sounds that arouse and stimulate me whenever I visit.

Especially the Golf Courses.

My favorite venue will always be Shinnecock Hills.

In 1986, I attended my first United States Open Championship as an accredited media member, and I was overwhelmed by the experience.

It was, and still is, one of the most fantastic and most challenging golf courses I have ever reported from.

It traces its roots back to when the game of golf was birthed over four hundred years ago on the sunbaked fields of Edinburgh, Scotland, amid the gorse and thistle-populated links of Scottish shores and sprinkled amidst the inlets and estuaries that abutted the Firth of Ford on the North Coast.

Wind and rain, sleet and hail fashioned the barren, sparse, and sandy linkslands that first spawned the sport of Golf,

Shinnecock was fashioned from the same mold.

The golf course, founded in 1891, is one of the most memorable and historical golfing institutions in the United States.

It is the oldest incorporated golf club in America, the first to admit women to membership, the oldest clubhouse in the United States (1892), and one of the five founding member clubs of the United States Golf Association (1894).

It also hosted the second United States Open and United States Amateurs held in 1896.

The place reeks of history, and I vowed I would do so if I ever returned and got to play the course.

I got my wish in 1995 when the Open returned to Shinnecock.

By then, a seasoned hand who knew the ropes and my way around tournament rules and protocols, I packed my clubs to New York and laid my plan in advance.

I would stay over a few days after the tournament, play Shinnecock, travel a few miles across the island, and play at The National Golf Links, which, like its neighbor, is cut from the same historical mode as Shinnecock and is one of the greatest but most exclusive golf courses in the world.

However, unlike its neighbor, the membership abhorrer publicity does not allow the general public to enter the property, does not entertain outside tournaments, and has never hosted a United States Golf Association or PGA Tour Event.

Billed as the Snobbiest Golf Club in the Country, the urban legend on why a club of its stature and pedigree does not hold significant tournaments is that the membership does not want golf fans from anywhere in America wearing their golf shirts with its distinctive logo embroidered on the front pocket.

I pulled many strings to get our tee times and was excited to experience and play two of the country’s oldest and most superb golf courses back to back.

Alas, it was not to be.

I played well at Shinnecock, but it was a brute and wore me out with its demanding test on every hole.

My partner in crime, a fellow writer whose excitement about playing matched mine but not nearly as accomplished, was also beaten up, exhausted, and shattered from the exacting test, cried uncle, and begged off our tee time for tomorrow, vowing never to play golf again.

So, we packed it in, nursed our wounds, bruised egos, and aching backs, and retired to the historic clubhouse high on the bluffs overlooking Shinnecock Bay and the Atlantic Ocean for a cold beer and memories of what might have been.

Like all those golf fans from Middle America, I have never set foot on one of the most esteemed and respected courses ever built, nor do I have a logoed golf shirt proclaiming my attendance there.

All I brought home was a bumper sticker proclaiming in capital letters: I LOVE NEW YORK.

CYPRESS POINT GOLF CLUB, Pebble Beach, California, designed by Alister Mackenzie in 1928, is rated No. 2 globally and 1 in California.

The central coastal region of California has a special place in my heart and holds many magical charms and memories.

My earliest childhood recollection in life is of being four years old, riding on my father’s handlebars as we pedaled downhill towards Fisherman’s Wharf, living in Monterey while he attended the United States Army’s Foreign Language Center after World War Two and the sights and smells of the ocean still linger in my sub-conciseness with permanency that remains to this day.

My mother’s cousin was the Administrator-Caretaker at Will Rogers State Park in the Santa Monica Mountains and lived in the old cowboy philosopher’s stately mansion, which we often visited in the summer, and I learned to surf the beaches of Pacific Palisades.

I attended Basic Training in the United States Army while stationed at Fort Ord, California, in Seaside, on the Monterey Peninsula abutting the Pacific Coast shoreline.

I spent my Honeymoon at Pebble Beach Resort, visiting and playing golf on the stored Links.

I attended and broadcast four United States Open Championships, held at Pebble Beach in 1972, 1982, 1992, and 2000.

Our first family vacation after I was married and had children was Southern California, Disneyland, The Pacific Coastal Highway, Sea World, and Monterey, California, where I showed my kids the house where I grew up.

I’ve always considered myself a California kid and embraced the laid-back surfer vibe even though I’ve lived most of my life in Utah.

However, the crown jewel of my involvement with Southern California was through my daughter Sarah.

She began her collegiate experience at the University of Utah while working for the Utah Grizzlies of the Eastern Hockey League.

Sarh amplified her marketing experience by volunteering for the Good Will Games in New York City and the Summer Olympics in Sidney, Australia 2000.

After accepting a position as assistant to the Marketing Director for the Long Beach Ice Dogs, which competed in the West Coast Hockey League, she moved to Long Beach, California, and continued her education at Golden Gate College.

Sarah progressed to Special Affairs Coordinator for the Los Angeles Clippers of the National Basketball Association before accepting the Marketing Director position at Pebble Beach Corporation and moving to Pebble Beach, just off a seventeen-mile drive in Monterey.

I was in heaven when we visited, and I got to play all the courses on the peninsula except one, Cypress Point Golf Club, the No. 2 ranked course on the planet and generally considered the most exclusive private club in the world.

One day during a visit, on a chance, I called the course and asked for the Director of Golf.

I explained who I was and asked about playing privileges usually extended to PGA Professionals.

He graciously explained that the club allowed one foursome of PGA Professionals a week outside playing opportunities on Monday afternoons.

Those positions were filled for the current week, but there was one spot for the following Monday if I was available, which, unfortunately, I wasn’t, as I was going home in a few days.

He gave me his name and phone number and told me to call the next time I was in town.

I thanked him and said I would.

Two months later, Sarah accepted a marketing position with the New Orleans Hornets of the NBA and left California, never to return along with any chance I had to play the greatest Golf Course west of the Mississippi River.

When I asked her later why she would leave the land of milk, honey, avocados, and palm trees waving in the setting sun, she remarked, “Pebble Beach is a great place to visit but a bad place to work.”

It was probably because of all the freeloading guests and family members she had to put up with as a nursemaid on Monterey’s many golf courses and beaches.

Regardless, I never got another chance to play the greatest golf course ever built on the West Coast on the United States.