“Memories of your past are the chronicles of your identity.”

It was worse than anything I had ever seen, could make up, or been part of, and without question, it was awful.

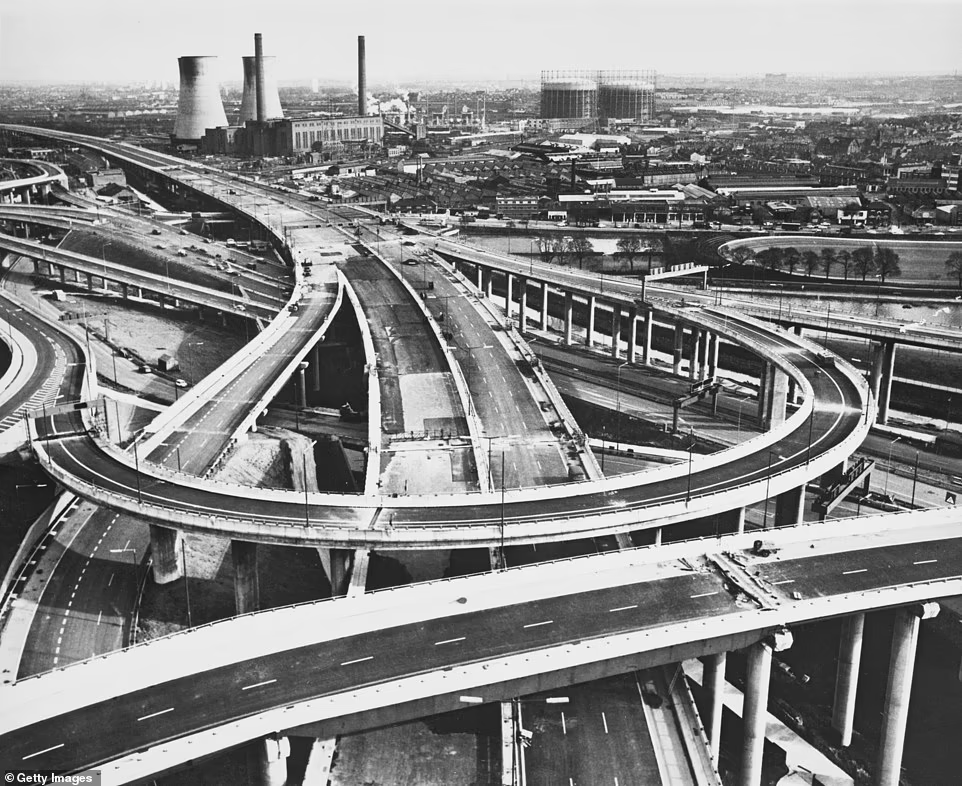

The cacophony of noise from the constant blaring and honking of horns, the grumbling clamor of internal combustion engines, and the reek of fumes from the exhausts of hundreds of motor vehicles was foul and unpleasant as the roadway before me collapsed into a single lane squeezed together, bordered by a phalanx of orange cones.

I was stuck in stop-and-go traffic, with no way out and nowhere to go but forward.

It called to mind a colony of ants, returning to their nest, queued up, end-to-end with faceless, nameless creatures crawling before me as shimmering reflections, glaring hot off the windshields that encircle me, draw attention to the piles of rubbish, not unlike scat churned out from a procession of mechanical beetles, scattered indiscriminately alongside the cracked and uneven pavement below.

The congestion was massive, as cars and trucks of every shape and size kept coming and coming, seemingly from every direction, entrance, and on-ramp, adding to the pent-up bottleneck without pausing in their efforts to enter the impasse and onslaught of uninterrupted traffic.

It was September 1999, and I had just arrived at Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts, had picked up my rental car, and was on my way to the 33rd Ryder Cup Matches when I got trapped in traffic.

I was traveling on assignment to the biannual competitions held on the storied links of the Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, a tony, fashionable, and well-heeled suburb southwest of Boston.

The “Battle of Brookline” would be contested at the Country Club of Brookline between Team Europe, captained by Mark James, and Team United States, captained by Ben Crenshaw.

The “Battle of Brookline” would be contested at the Country Club of Brookline between Team Europe, captained by Mark James, and Team United States, captained by Ben Crenshaw.

The Country Club, one of the oldest private clubs in the United States and a founding member of the United States Golf Association in 1894, is steeped in old-school rituals and tradition and would prove a worthy test for the best international players in the world.

Getting there was proving problematic.

The streets of Boston and the jumble of roads connecting Boston Harbor, the Shipyards, the Waterfront, and the City of Boston, one of the most populous capitals in New England, were pieced together long before automobiles were conceived and built.

The City itself was one of the first colonies in New England, founded in 1620 by English Puritans seeking religious freedom.

Boston is also considered the birthplace of the American Revolution and National Experience.

Nevertheless, as the town grew and expanded outward from the coast, harbor area, and marketplaces, migrating towards the city center, road traffic became extremely congested with wagons, horses, handcarts, and later motor vehicles as the Industrial Revolution commenced.

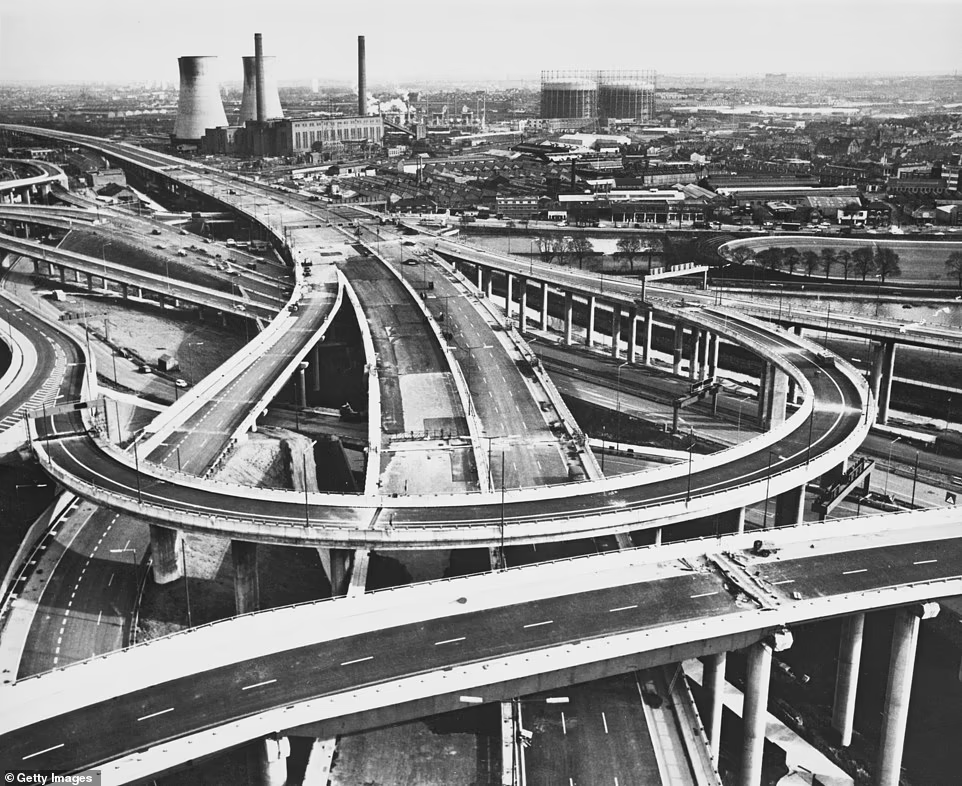

Central Artery Ring Road was conceived and constructed in 1951 before strict federal highway regulations were developed and implemented during the Eisenhower Administration.

The road would connect the coastal areas, the expanding and increasingly engaged Logan Airport, and downtown Boston proper.

However, from the start, the Ring Road needed help with problems.

The roadway was a disaster, with tight curves, excessive entries and exits, narrow access ramps without acceleration lanes, and ever-increasing automobile traffic.

When it opened in 1959, the road carried 75,000 vehicles a day; in the early 1990s, more than 200,000 traveled regularly, making it among the most congested highways in North America.

Traffic crawled back and forth for more than ten hours daily, and the accident rate was horrendous.

Wasted fuel, time constraints, altercations, and late deliveries all compounded the problem.

The Massachusetts Turnpike Authority (MTA) proposed new construction on a reworked Central Artery/Tunnel Project to relieve the congestion.

The Central Artery design, AKA, (The Big Dig) became one the most significant, most challenging highway projects in the history of the United States, comparable to the grand projects of the last century, not unlike The Panama Canal, the English Channel Tunnel, and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

The design took thirty-five years to complete but reduced traffic and improved mobility in one of America’s oldest, most congested major cities.

It also contributed to Massachusetts and New England’s economic growth while improving the environment for the entire region.

Unfortunately, the construction was ongoing and in progress, and I was stuck in the middle of it all, with my timeline for the day rapidly fading.

Unfortunately, the construction was ongoing and in progress, and I was stuck in the middle of it all, with my timeline for the day rapidly fading.

I planned to check in to the media Hotel, pick up my press credentials and parking pass, sightsee around Boston for a while, and then hit the road for the second segment of my outing.

I had purposely arrived in town a few days before the tournament to visit the New England coast, delve into my personal history, and explore the celebrated City that had contributed so much to our nation’s storyline.

However, my schedule was shot to pieces, so after checking in, dropping off my broadcasting gear, and unpacking, I quickly reclaimed my rental car and headed back out on the road, traveling south on I-495, away from the City, hoping to uncover my past.

***

I was born to goodly parents on Saturday, September 8, 1945, at 11:45 a.m. in Morton Hospital on Lakeview Avenue in Taunton, Massachusetts.

Taunton, one of the oldest and most time-worn communities in the United States, is usually a sleepy little hamlet located in the southeast part of the state, adjacent to the town of Plymouth, neighboring Cape Cod, and the iconic and scenic Martha’s Vineyard.

One of the oddities that have occurred throughout my life is I have had to answer the question of why I was born on the East Coast of America curiously so, when you consider the fact I am the descendant of Mormon pioneers and have lived, except for university and military service, the entirety of my life in Utah.

Massachusetts, to most Westerners, seems like a foreign country.

I do not know why this subject has come up as much as it has during my life, and maybe, expecting the reaction, I have been a little too sensitive and defensive about always having to explain the reason.

The question concerns the fact that many people have open-ended conversations with others.

“Where are you from?”

“Where were you born”

I would always engage in an extended dialogue about the why and the how.

Anticipating the question, I often hesitated and said I was born in Utah, which avoided the question.

The answer, on reflection, is quite simple and of interest when considering the times.

I was born a classic baby boomer, grew up a child of the fifties and sixties, and I am the offspring of parents and grandparents who, as members of the Greatest Generation, endured two world wars and the greatest depression humans had ever endured.

It was a time of great turmoil and introspection for a tattered and tired group of older Americans looking for an improved and more peaceful lifestyle for themselves, their children, and their families, and the world I was thrust into during this tumultuous and disorderly era of global unrest.

Theirs was a cohort that had prevailed and survived the horrors of the holocaust and understood on a profoundly personal level how selfless, just, and admirable the community of nations was to have escaped the worst aspects of human nature and behavior that could have affected the entire global population with catastrophic and disastrous results.

My parents included.

It was during this chaotic period of world history that my father, Morice Ned Waters, was a soldier in the United States Army awaiting overseas shipment to the European Theater during the last days of World War II and assigned to Camp Myles Standish, named after the first military Commander of the Continental Army and one of the original immigrants to America who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620.

Commander of the Continental Army and one of the original immigrants to America who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620.

Established in 1942, the War Department created the military installation in Taunton, Massachusetts, on the eastern seaboard of the United States, as a staging area for overseas replacements and as a prisoner-of-war facility for German soldiers captured during the war.

When German forces surrendered to the Allies in May 1945, effectively ending the war in Europe, my mother, Katherine Goodliffe Waters, pregnant with me and nursing my older brother Jerry, relocated from Utah to Oakridge, Tennessee, to be with her mother, Leah Goodliffe, her stepfather Weldon Peterson, along with her younger sisters, Glenna, Iris, Shirley, and Marilyn, and to be somewhat closer to my father, then stationed in Taunton, awaiting orders.

My grandfather, a structural engineer, was assigned to the Clinton Engineering Works, a sub-division of the Manhattan Project, the ultra-secret atom bomb project.

Where American scientists were frantically trying to complete the project before opposing forces could build their atomic bomb.

With this in mind and anticipating the war’s end, my mother, with unstoppable independence and self-determination, just twenty-three years old and five months pregnant, packed up my brother Jerry and left Tennessee.

She took the train to Taunton, unaccompanied in wartime, traveling alone, leaving behind her mother, sisters, and support group.

To reunite with my father and be together as a family, when I arrived in this uncertain and tumultuous world.

With the fighting in Europe over, coupled with the unconditional surrender of German forces, President Harry Truman turned his attention to the Pacific and, in August 1945, dropped the atomic bombs on Japan, which effectively ended American involvement in World War II.

Thirty days later, I was born, and Taunton, Massachusetts, became my birth city and the everlasting notation on all my official records.

With the most destructive war in history almost over, my father was assigned to the US Army Language School in Monterey, California, facilitating packing and moving across the country.

Two months later, and with a stoutness derived from their pioneer heritage, my parents loaded my brother Jerry and me, bundled up against the harsh winter cold, into a 1938 Chevy held together with baling wire and tape.

In the deepest winter months of 1946, with prayers to the heavens above, set forth across the United States on two-lane, snow-covered roads bound for Utah.

With little or no lament, our family left Massachusetts and the East Coat of the Continental United States behind, bound for my grandparents’ home in Mount Aire, Utah, a housing suburb in Millcreek, Salt Lake County, where we could stay and live out the remainder of the war.

With little or no lament, our family left Massachusetts and the East Coat of the Continental United States behind, bound for my grandparents’ home in Mount Aire, Utah, a housing suburb in Millcreek, Salt Lake County, where we could stay and live out the remainder of the war.

As the three of us settled in with my grandparents, my father left us behind once again.

He continued on his journey to California, serving out the remainder of his tour of duty while we understandingly awaited his return.

Meanwhile, the circumstances surrounding my birth and my brief sojourn to Massachusetts had profound and lasting effects on my psyche, which would linger with waning recollections for the remainder of my life, the whereabouts I would often revisit emotionally, mentally, and subconsciously.

However, the opportunity to visit those recollections physically would have to wait for another fifty years.

***

It was dark when the divided freeway, US 44 from the North, narrowed to a two-lane state highway.

A sign on the unlighted MA 40 abruptly illuminated, revealing the exit to Taunton.

Startled, I quickly hit the brakes to disengage the cruise control and took the exit way too fast.

As I applied the brakes, the crossroad’s modest interchange surprised me with its small scale and absence of buildings.

The north side of the intersection contained a Howard Johnson’s motel with an attached bar and grill, while a combination convenience store and gas station filled the other side.

A darkened, modest two-lane road bisected the middle of the intersection, offering a tree-lined passageway heading south into the countryside’s blackness.

Confused and wondering if I missed the main exit, I stopped at the gas pumps, hit the dome lights, and checked my map.

Thinking I had better ask directions, I unbuckled my seat belt, got out, and stretched my legs before entering the store.

The 7-11 clone’s cookie-cutter layout in the backwoods countryside of Southeast Massachusetts unnerved me with its sameness and uniformity, as even the beer cooler was positioned in the exact spot as every other location in America.

I could be anywhere in the country, except for the unexpected welcoming from the solitary attendant, who smiled and said, “Haw, may I hape you” in the broadest, deepest Bostonian accent I have ever heard or could fathom.

Taken back, I reacted, “I’m looking for Taunton,”

“This is Taunton,” she answered, still in that very discernable and heavy regional dialect.

That led to a further inquiry, “Then where is the town?” I questioned.

“It is down the road about a mile,” she replied,” still in character and pointing South.

Unnerved, I countered with, “I was born here.”

“So was I,” she rejoined, breaking the awkwardness of the exchange and opening up a more cordial dialogue about how and why I was here, what I was doing in the middle of nowhere looking for the Hospital where I was born, all while conversing with a distinctly Utah twang.

As we wrapped up the chit-chat, seemingly in different languages, I asked, “If there were any hotels close by,” and with typical New England bogusness, she pointed across the street while suggesting, “Anything in town would probably be closed.”

I thanked her for the information and courtesy, ventured across the street, checked in to the nearly vacant motel, and promptly retired to the bar for something to eat and drink.

At the same time, I contemplated the next step in my journey, wondering once again if going home would be a disappointment, a blessing, or liberating.

I would soon find out.

Morning came early with it, a bottled-up eagerness to begin the day.

With practiced movements, after many years of golf tournaments and broadcast assignments worldwide, I quickly showered, dressed, and left my key on the nightstand.

Retrieving my car and following the helpful clerk’s instructions, I took the unmarked road to Taunton with thoughtful anticipation, under the early glow of a brilliant New England fall day, in search of the hospital where I was born, which had bequeathed me the gift of life and the story of my beginnings.

***

Taunton, Massachusetts, founded in 1637, is one of the oldest towns in the United States.

The settlement, established and developed by members of the Plymouth Colony, is positioned on the confluence of the Taunton and Mill Rivers, which wind their way through the area on their southern journey to Mount Hope Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

Those early colonizers retained the name of Taunton to honor their ancestral home in Taunton, Somerset, England.

Like most early colonial outposts on the East Coast of America, Taunton was fashioned as a village square whose built-up walls encompassed the colonists’ modest dwellings.

The rectangular square was fortified to protect the colonists from Indian attacks while keeping their livestock in check.

As the town grew and prospered, the village square soon developed as a communal area jointly held by the village and its inhabitants collectively to gather socially, engage in outdoor activities, and barter goods and services while reflecting on current and national affairs.

The village commons, now officially recognized as The Taunton Green, soon expanded as the town’s commercial, business, and industrial center.

Sawmills and gristmills populated the region, using nearby rivers for transporting goods and merchandise, and Taunton soon became a central shipping point for inland rural parts of the country.

The Green also served as a gathering place and training center for military maneuvers during the Revolutionary War.

The Green also served as a gathering place and training center for military maneuvers during the Revolutionary War.

A large monument now graces the center on The Green, honoring and commemorating American soldiers who lost their lives in service of their country.

Thanks to directions from my new friend at the convenience store, that monument and The Green encircling it became my destination, along with the many business-related buildings surrounding the town center, including the hospital.

***

Like many motivated and inquisitive youngsters with a family background of means, Marcus Morton, born in 1784, left Taunton at fourteen, seeking his education, fame, and fortune.

He found all three, receiving his degree from Brown University.

There, he was a classmate of John C. Calhoun, who would remain a lifelong friend, mentor, and future Vice President of the United States.

Morton continued his education, earning law degrees from Brown University and Harvard.

Returning to Taunton, he was admitted to the bar and opened his law practice in 1807.

Achieving success, he soon married and raised twelve children.

As was customary in that era of American history, Morton constructed a sizeable antebellum mansion to house his growing family, where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Overseeing a bourgeoning and successful law practice, he entered politics, serving as a Delegate to the Continental Congress, a stint in the United States House of Representatives, a Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, and two separate terms as Governor of the State.

Morton passed away in 1864 as one of the most celebrated and respected residents in the history of Taunton.

He died in the house he built, lived in, and raised his family in, fronting the historic Taunton Green, a setting he passionately helped develop, expand, and represent in the uppermost public service halls.

He died in the house he built, lived in, and raised his family in, fronting the historic Taunton Green, a setting he passionately helped develop, expand, and represent in the uppermost public service halls.

Upon his death, Morton’s family generously donated his sizeable and beloved home to the City of Taunton.

Where that large, stately mansion, which pre-dated the Civil War, with its massive columns supporting an elegant wrap-around front porch, façade, and portico, looking out towards the imposing monument honoring Taunton’s contribution to America’s military history, became the original building of Morton Hospital and Medical Center and was an easy place to find.

In that remolded manor of a grandee of American Revolutionary history, I finally uncovered the whereabouts of my beginnings and the place where my Mother brought me into this world.

My lifelong search was drawing to a close.

As I climbed the steps of the covered veranda and pushed my way through the imposing front entrance, I was instantly met with the heady scent familiar to all hospitals.

Almost immediately, a nurse confronted me, seemingly straight out of central casting, dressed in a formal, white starched uniform, including the traditional nurse’s cap and polished white leather shoes.

With a forceful and taciturn authority, she solicited, “May I help you?”

Anticipating the exchange, I had rehearsed my reply over and over in my head ever since that day in Salt Lake months ago when I was visiting my Mother and informing her of my mission to research the background of my birth and find out the history of the Hospital where I was born.

I also strongly expressed to my mom the extraordinary meaning and importance of pilgrimage for my identity and state of mind.

The nurse’s reaction to my rushed and nervous response to the sequence of events leading me to this moment in time and all the drama it entailed was staggering in its compassion and thoughtful empathy.

Her demeanor changed immediately as she smiled, warmly embraced me, and instantly acknowledged and accepted me as a fellow native and Tauntonian.

She graciously took me on a tour of the Hospital, introducing me to administrators, nurses, doctors, technicians, and even the custodians.

She escorted me into the maternity ward where I was born fifty years before in a crowning and highly emotional moment of a perfect reunion.

It was everything I could have dreamt a homecoming might be, and the entire ordeal was immensely satisfying.

It justified my decision to return home and provided closure to questions that had shadowed and beguiled me since childhood.

Discovering my place of birth and the backstory of the events and circumstances that contributed to that corroboration will always remain a cherished highlight of my return to New England.

After saying goodbye and expressing my heartfelt thanks to the hospital staff for their politeness and thoughtful consideration, I stopped at the gift store looking for memorabilia on sale.

I purchased postcards of the Hospital and a quartz glass replica of Marcus Morton’s ancestral home to remind me of the journey to my birthplace.

With my most important task fulfilled, I took a leisurely tour around The Taunton Green and marveled at its fountains, monuments, and the slice of Americana they represented.

Their long, unique history contributed so much to the story of our nation’s past, which I now share with all of Tauntonian, past and present, and in a modest and valued way, will stay with me for the rest of my life.

This entire episode reaffirmed my affinity for the East Coast of America, particularly Massachusetts, even though my sole exposure to the region was my birth.

As far-fetched as it sounds, I am now a symbolic New Englander.

This makes me wonder why so many Westerners are hesitant about visiting or going on vacation to the East Coast.

Being in the recreation business, I have seen real-life examples of The Great Divide that separates this country into separate and distinct regions, which exist and populate people’s minds and viewpoints.

The East vs. West quandary poses a real dilemma for consumers, especially Golfers when deciding where to travel and spend their leisure dollars.

People living west of the Mississippi often look southwest towards Southern California, Hawaii, Mexico, and Central America when going on holiday, not east, and that is a conundrum that has yet to be overcome or dismissed.

I have repeatedly voiced these concerns when attending marketing summits for the PGA and Golf Writers Association to little or no avail.

When I tell people I was born on the East Coast, in a small, unassuming village, they look aghast and imagine a distant wilderness somewhere far away, a perception I have lived with my whole life.

***

Famished and contented with the outcome of my quest, I left Taunton behind and headed east to the coast, looking for nourishment and the Ferry to Martha’s Vineyard.

The Vineyard, informal slang for Martha’s Vineyard, had always fascinated me with its avant-garde charm, allure, and sophistication.

The East Coast’s version, reminiscent of the vibrant arts colony in Malibu, California, attracts artists, craftsmen, and celebrities.

The movie Jaws was filmed on the Island, which is well known for its public attractions, beaches, lighthouses, and laidback community culture.

It is also a place I have always wanted to visit.

While I pondered my next move, waiting for the ferry and its half-hour ride to the Island, nursing a glass of Samuel Adams and wolfing down a bowl of clam chowder, I thought back to a vow I had made to myself long ago, the first time I returned to the East Coast of America as a grown man.

The occasion occurred during the 1986 United States Open Championship, contested at Shinnecock Hills in South Hampton, New York, when I first began broadcasting radio nationally.

As an accredited media member of the Golf Writers Association of America, I covered the Major Golf Championships on the PGA Tour.

I traveled to cities that were hosting those tournaments.

As a Utah greenhorn visiting the Big Apple for the first time, I was excited to see and explore a city that never sleeps.

The train to Penn Station and downtown New York City stopped at the Golf Course on its way to the city.

To my everlasting regret, while captivated with announcing my second Major Championship on the PGA Tour, and first outside the Mountain West, I neglected to take the short trip into the City, a mistake I would not make again.

Waiting for the Ferry, I revisited my promise never again to abandon my pledge to visit, sightsee, and explore the incredible diversity, historical landmarks, and well-known sights and scenes scattered throughout this great country.

I will use the privilege bestowed on me to travel and visit this nation‘s great cities and localities as part of my employment, covering and airing major golf championships on coast-to-coast radio.

***

I finished my beer, boarded the ferry, and devised my strategy.

I was not due back to the Country Club and Media Center for my on-air responsibilities until tomorrow night’s Opening Ceremonies, so I had an extra day to explore the shoreline.

I would follow the venerable Kings Highway up the East Coast.

This well-traveled thoroughfare, also known as the Old Post Road, has connected central New England’s commercial regions of farms, orchards, workshops, factories, and warehouses to Boston Harbor since colonial times and is packed with remarkable places and exciting things to do.

If I saw something I liked, I would stop.

If I got tired, I would rest.

If I got hungry, I would eat.

I called on most of the small towns on the Atlantic Seaboard, including Sandwich, Plymouth, Kingston, Revere, Quency, Gloucester, Salam, Manchester-By-Sea, and Essex, all historical sites that contributed to our colonial past.

I visited boutiques, lighthouses, antique stores, book shops, Plymouth Rock, The Mayflower, and other tourist attractions; I saw them all, and, on an interesting side note.

At every pause was the obligatory gift shop and concession stand, which served soft drinks, confections, trinkets, and other items, including clam chowder in little cups with plastic spoons.

Sampling this regional staple’s distinctive flavors, textures, and seasonings at each stop became a rite of passage.

In an act of contrition, I blew right past Boston and just kept going to see how far up the coast I could make it, only stopping if I saw something interesting.

When I finally did call it quits and pulled off the highway to park and find a place to stay, I found myself caught in the glare of the revolving beacon light, signaling out from the celebrated lighthouse safeguarding the rock-strewn beaches in the age-old seaport of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Tired, worn out, and feet hurting, I checked into the Inn perched on the harbor’s embankment, where I relaxed in the connected café.

Happy to be out of the car and weary of clam chowder, I wolfed down a cheeseburger and French fries while relishing a cold beer and then stumbled to my room.

I collapsed into bed, exhausted and done by the day’s activities but enthralled with the consequences of what I had seen and experienced on a day of unbridled satisfaction and fulfillment.

I had visited much of the fabric of America’s colonial foundation, caught glimpses of our nation’s past, viewed long-ago images, and learned sufficient history for one day.

***

The following morning, sitting in the comfort of the Inn’s coffee shop, overlooking the matchless panorama of the wave-swept waterfront in Portsmouth, feasting on homemade buckwheat hotcakes with real maple syrup almost made up for the strenuous outing I endured yesterday.

Still, I was not finished with my journey.

One of the motives for my extended excursion up the east coast of New England was arriving at this final setting.

I was shooting for Kennebunkport, Maine, farther up the coast, but tired of driving, I settled on Portsmouth, which was fine as my concluding destination.

I visited all the shops and tourist attractions I wanted to see yesterday.

I was sick of clam chowder and eager to visit the heartland of rural, present-day, old-fashioned New England, with no shopping or sideshows to distract me.

Just a leisurely drive down the scenic byways and country roads while eschewing the freeway, on a straight shot across Vermont, heading for Concord and the images of Norman Rockwell sights and scenes along the way.

I was hunting for rustic, unspoiled farms, picture-perfect small towns, old-fashioned watermills, covered footbridges, and finally, a restful drive through enchanted, overlooked villages of the golden days of New England’s colonial past.

Most of all, I wanted to witness the breathtaking splendor of autumn leaves draped across the canvas of a perfect New England fall day in all its pastoral glory.

I could not wait, so after breakfast, I loaded up and headed out, impatient to wrap up the campaign I started yesterday but immensely pleased with my efforts.

I had discovered my roots, visited most of the eastern seaboard’s historical landmarks and attractions, and visited the lion’s share of the original thirteen colonies.

I was now on my way to behold one of nature’s genuinely scenic, most picturesque wonders of creation.

It called to mind that old refrain and limerick, “Paris in the Springtime, New England in the Fall, and I’ll take New York City anytime at all.”

My desire to see, experience, and celebrate all three of these spectacular marvels of geography was about to come to fruition.

I caught the US 4 out of Portsmouth to Northwood and the junction of old Turnpike Road connecting the coast, where it forked off to Concord, now US 202.

***

The long, gentle, meandering two-lane road winding through the fall landscape was picture-perfect and a microcosm of everything I came to New England to discover and celebrate.

More than uncovering my history and back story, the regal countryside of Central New England fulfilled the promise of my coming home.

In a textbook case of reality exceeding expectations, the majesty and spectacle of colors emanating throughout nature’s untouched and spectacular landscape put the finishing touches on a perfect outing amidst New England’s breathtaking scenery.

Satisfied and pleased with my encounter but tired and eager to return to work, I rejoined the freeway at Concord, merging onto I-93 and a direct route back to Boston.

***

The Media Hotel, centrally located in downtown Boston, was just off the freeway.

I hurriedly parked my rental in the guest lot, left my parking pass on the dashboard, and locked the car I would not revisit until Sunday evening.

Then, I took the elevator to a room untouched and unseen for three days.

I dropped off my travel stuff, quickly changed my shirt, grabbed a windbreaker, notebook, and tape recorder, headed out the door, and took the elevator to the lobby, where I caught the shuttle to Brookline’s golf course and media center.

Before tomorrow’s opening kickoff, I would meet, mingle, and conduct background interviews with the twenty-four most talented golfers.

The brainchild of Samuel Ryder, a wealthy nineteenth-century merchant and golf enthusiast, conceived the idea of friendly matches between Golf Professionals in Great Britain and the United States.

The games began in 1927 and alternate between Europe and America every two years.

Players compete for pride in their country and team rather than personal glory and financial enrichment.

The matches offer a format different than any golf tournament played on professional tours, and the selection process for players is long and demanding.

To be picked for either team is often considered the pinnacle of a golfer’s career.

The Ryder Cup is a different animal.

Unlike regular tour events, match play is a hole-by-hole contest over eighteen holes.

Matches are determined by reckoning each hole.

Matches are determined by reckoning each hole.

A player either wins, ties, or loses the hole, and personal scores for players are not recorded.

Matches are eighteen holes; the player who wins the most claims the match, and each match is worth one point.

The first team to fourteen and a half points wins the Cup.

The Cup’s format calls for four two-man teams, playing morning and afternoon the first two days, and individual play with all twenty-four contestants competing on Sunday, with fourteen points total available.

Strategy plays an integral part in the contest, matching talent and individual strengths and weaknesses to determine who plays whom against whom, adding suspenseful intrigue to the proceedings.

The games are very partisan, with strong emotions and national furor involving both sides.

Anticipation for the Ryder Cup, one of golf’s most extraordinary events, set in opposition twelve of the best players from Europe against twelve of the best Americans in biennial competitions, was palpable and raging crazy and wild throughout the city.

When I got to the golf course, controversy was already brewing.

The American team was still smarting from their narrow loss in the previous Cup’s contest at Valderrama, nestled high in the foothills off the southern coast of Spain, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, had not done themselves any favors in the weeks leading up to this season’s matches.

Americans had been trash-talking the Europeans in the press before this year’s event while disparaging the Europeans and their lack of talent.

Payne Stewart said, “On paper, they should be caddying for us.”

While Jeff Maggert added, “Let’s face it, we’ve got the twelve best players in the world.”

Which, based on world ranking, was true.

The United States team was strong, with ten players ranked sixteenth or better in the world, including three of the top four, only excluding Europe’s No.1, Scotland’s Colon Montgomery, who was bearing the brunt of negative media and hostile reactions from American fans, and European’s were upset with the public’s discussion and abuses thrown their way.

Golfers are a proud lot, especially when their country is involved.

Pre-tournament exchanges were frosty, and given Boston sports fans’ enthusiastic nature, edginess loomed in the future.

I went to bed that night expecting fireworks in the morning, as the “Battle of Brookline“ was about to begin.

I woke up early, sore and stiff from the previous day’s drive, so I decided to walk through the neighborhood to loosen up.

I grabbed a bagel and coffee from the hotel’s breakfast bar and entered downtown Boston’s teeming bedlam.

Imagine my astonishment when a large ground marker, signifying an entry point for the Freedom Trail, was just outside my hotel’s entrance.

Curious, my sightseeing sorties just got another jolt and call to action.

The Freedom Trail, conceived in 1951, is a pedestrian-friendly path winding its way around and through Boston’s abundance of historic landmarks noteworthy to the history of colonial America.

The National Parks Service oversees the pathway, which offers tours, maps, and summaries of sites important to United States history.

Commemorative markers embedded in sidewalks along the way guide and inform visitors of the site’s stories and importance.

Commemorative markers embedded in sidewalks along the way guide and inform visitors of the site’s stories and importance.

Notable locations included the Massachusetts State House, Park Street Church, Boston Common, Kings Chappel, and Burying Ground, the Statute of Ben Franklin, Paul Revere’s House, Bunker Hill Monument, Old North Church, the Boston Massacre Site, the US Constitution, and others.

You may stroll at your leisure, take pictures, pick up literature, and spend as much time as you like at each position.

An added yet contemporary bonus to my morning outing was a visit to the Bull and Finch Pub, better known as Cheers, and the setting of the popular TV show, familiar to all America, located on Beacon Street, adjacent to the Boston Commons, and just off the trail.

Pleased with my opportune discovery and the added supplementary trove of historical facts and sites of my birthland, I returned to my hotel prepared to report on the day’s contest.

A significant shortfall of broadcasting from the East Coast to other time zones across America, especially for a limited-field event like the Ryder Cup, is the lack of timely action to comment on.

Morning and afternoon drive broadcasts are little more than a regurgitation of facts, details, and background already known to most listeners.

The biggest news to present on the day’s proceedings was the continued and increasingly hostile verbal assaults on Colon Montgomery, who was now under police protection from the rabid New England attendees who were taunting him unmercifully every hole.

By the time I returned to the golf course, the morning matches were underway, and with no discernible results to report, I settled in to watch the day unfold.

I have constantly voiced my opinion to all who would listen; the best place to watch a golf tournament is from the media center, not following along and walking the course.

Seeing anything with people packed around the greens and tees is virtually impossible with large crowds following the day’s play.

The media center offers constant updates of unfolding content, big-screen TVs carrying all the news, food, and beverages readily available, and the most significant benefit of all, accessible and clean restrooms.

My advice for big tournaments is to stay home and watch them on TV, but I wander off-topic.

The Europeans, upset with the unfavorable press and a loud, hostile crowd, got off to a fast start on Friday morning.

The day’s proceedings unfolded like this:

Morning results were 2 ½ points for Europe and 1 ½ points for America.

Afternoon results were Europe, 3 ½, points, America ½ point

The totals for the first day were 6 points for Europe and 2 points for America.

Saturdays Matches.

Morning results

Tied, two each

Overall

Europe 8 points, America 4 points

Afternoon results.

Tied, two each

Overall

Europe 10, America 6

The Americans were in serious trouble, and Captain Ben Crenshaw knew it.

In the history of the Ryder Cup, no team has ever returned from two points down on the last day to win the Cup; four points was virtually impossible.

Knowing he needed a different strategy, Ben Crenshaw front-loaded his lineup, with his best players going out first thing in the morning.

It worked; America won the first six matches of the day and now led for the first time all week, 12-10, with six matches still on the course.

The two teams split four matches, and the US still led 14 points to 12 points.

The US needed just a half point to claim victory in the most remarkable comeback in Ryder Cup history, and the crowd was going crazy and swelled in size as they followed the last two groups on the course.

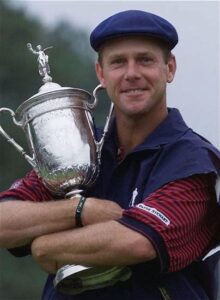

The final two matches were between America’s whipping boy, Colin Montgomery, and the reigning United States Open Campion, Payne Stewart.

At the same time, Justin Leanord was squared off against Masters Champion Jose Marie Olazabal.

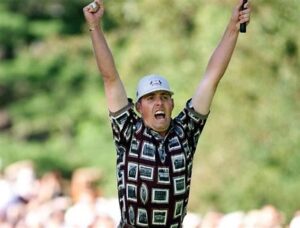

It came down to the last two holes, and when Leonard holed an improbable forty-foot putt, thinking the match was over, sent the pro-American crowd into a frenzy.

The partisan crowd of fans, wives, and caddies rushed onto the green in celebration in a severe breach of etiquette and unsportsmanlike behavior.

However, Olazabal still had a putt to tie.

He missed, guaranteeing the 1999 Ryder Cup belonged to America.

The final match, still on the course, came down to the final hole, and with the tournament outcome already decided, Payne Stewart, in an act of perceptive sportsmanship, while atoning for the mistreatment and insults Montgomery had suffered throughout the day, conceded Montgomery’s final putt, gifting the hole to the Europeans, making the final tally,

Europe 13 ½ points, America 14 ½ points

America had claimed the Ryder Cup on American Soil for the first time in four years.

With little time to reflect on the day’s triumphs, my goals realized, and the broadcast assignment completed, I took a final shuttle ride back to the hotel.

There, I hurriedly packed, checked out, found my rental, and followed the signs to the airport.

However, I had forgotten how bad the traffic could be and paid dearly for it.

I had allowed an hour to drive the three miles through the construction of the Big Dig, return my rental, and deal with the check-in for my flight.

I never made it, not even close.

I stood in line when my flight to Utah took off and left without me.

With no flights out of Boston to Salt Lake until tomorrow morning and those flights wholly booked, I was consigned to standby status with no car, no place to stay, and no options.

Hauling my luggage and radio gear behind me, I found the now vacant boarding gate for my flight to Salt Lake and searched for an unoccupied corner to hunker down for the night and maybe an early morning flight tomorrow.

I was tired and worn out, wondering what the future held, and depressed about spending the night shivering in the stale, airconditioned aroma of a dungy airport waiting area.

In that moment of despondency and little hope, all hell broke loose.

Airport personnel rushed everywhere: emergency vehicles, red lights flashing, racing about, and sirens blasting with ear-piercing rackets.

My empty boarding gate, which I had chosen for the night’s refuge, was suddenly filled with anxious and concerned people milling about.

Which included security, airline officials, firemen, and medical personnel.

The plane that had just left the airport, bound for Salt Lake City, and the very plane I was supposed to be on, had lost an engine on takeoff, circled out over the Atlantic Ocean, dumped its fuel, and was now returning to Boston to make an emergency landing with on one engine.

Another unpleasant incident was about to unfold.

After successfully landing with a single engine, the wounded plane taxied to the end of the runway and was quickly surrounded by emergency vehicles, ambulances, and fire trucks.

The passengers were loaded onto buses and soon arrived at the boarding gate where I was camped out.

To a person, they were shocked, stunned, and traumatized by the ordeal they just went through.

Ticket agents met them at the gate to reassure and console them while planning for their safety, well-being, and impending travel plans.

I recognized one of the couples exiting the boarding area and asked about their ordeal.

They suggested, very shaken, that they never wanted to fly on an airplane again, implying there might be room for me on the replacement list for tickets on the flight rerouted from Atlanta.

I approached the booking agent who was handling the vouchers for displaced passengers.

I told her my story of missing the flight on the doomed takeoff and showed her my unused ticket.

Her understanding of my plight manifested in her immediately booking me on the makeup flight to Salt Lake City, scheduled for first thing the following day.

My night of lounging in an empty airport waiting room was appreciably shorter and more comfortable.

In hindsight, my journey to Massachusetts, which began with the unbearable agony of being stuck in traffic, sandwiched with the anguish of knowing it could have been me on that disabled aircraft making a harrowing emergency landing, was nearing its conclusion.

The delights of my encounters on my getaway to the East Coast were, in no way, diminished by those two happenstances, and the essence of my journey was overwhelmed with the joyfulness of discovering my roots and realizing my existence.

Massachusetts and the village of Taunton will always be part of my character and the uniqueness of my personality for as long as I exist.

Epilogue

The Big Dig

The Central Artery/Tunnel Project was the largest and most challenging highway project in United States history, taking thirty-five years from start to completion.

Constructed for twenty-four billion dollars, plus interest to its stakeholders, the roadway shortens travel times for the 3.5 miles across downtown Boston and the harbor from 19.9 minutes to 2.8 minutes.

It can accommodate 300,000 vehicles daily by routing airport traffic from I-93 underground through the newly constructed Ted Williams tunnel.

The highway’s inauguration instantly reduced downtown Boston’s traffic congestion, significantly improving air quality and environmental conditions and reducing noise pollution.

The project significantly boosted economic development in Massachusetts and New England, creating parks, open spaces, and significant developments in nearby communities.

While laborious and painstaking, the massive undertaking saved the City of Boston, the surrounding communities, and the entire eastern seaboard from industrial and economic stagnation.

While restoring community viability, pride, and commerce to a proud and historically significant region of the United States.

The Big Dig did its job.

The Battle of Brookline

Americans won the 1999 matches with the largest comeback in Ryder Cup history, but their win was bittersweet.

The American team would not prevail again for seven years, losing the next three cups and nine out of the next eleven.

British and American media criticized American golf fans’ behavior at Brookline, explicitly citing their boorish and premature celebration on the seventeenth green after Justin Leonard’s lengthy putt.

Coupled with British players routinely mocked and abused by American sports fans.

It would also be the last international appearance for Payne Stewart, who tragically died in a plane crash just three weeks later.

For his generous gesture of conceding Colin Montgomery’s putt during the 1999 Cup and other acts of grace and compassion, the PGA of America posthumously established the Payne Stewart Award, awarded annually to the golfer whose values best exemplify the character, charitable mindset, and sportsmanship that Stewart demonstrated.

charitable mindset, and sportsmanship that Stewart demonstrated.

Stewart was one of six golfers twice winning the US Open and the Open Championship and was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2011.

His legacy endures.

Morton Hospital and Medical Center

The ancestral home of Marcus Morton, built in 1826 and donated to the City of Taunton upon his death, served as the solitary hospital in Southeastern Massachusetts from 1864 until 2006, providing essential health services to the residents of Taunton and its surrounding communities for over a hundred and forty years.

The stately and historical mansion shaped much of the history across the critical moments of Central New England’s development, and the residence was expanded and remolded in 2006.

However, the aging home and attached medical building caught fire during construction and burnt to the ground.

It was not replaced.

The plot of ground where it stood was razed over, and a new, state-of-the-art facility was erected on the site where I was born.

The medical center and Marcus Mortons’ imposing mansion and their legacy cease to exist.

Colasped in a heap of ashes, and all that remains of its memory is a glass replica of Marcus Morton’s regal and imposing family home.