The Life and Times of a PGA Master Professional

Hello Everybody:

My new book, A Golf Course Flowed Through It, is now available through all major booksellers, Amazon, and as a Kindle download, making it easily accessible to all of you.

In my latest effort, I reflect on aging, legacy, and self-discovery, emphasizing the importance of understanding one’s past and personal story.

I also chronicle my journey from a curious youth to a dedicated golf professional and broadcast journalist and the formation of Rocky Mountain Golf Enterprises and its associated businesses, including my teaching academy, golf schools, radio network, production, and travel companies.

My latest narrative intertwines historical and personal anecdotes, ultimately highlighting the significance of preserving and sharing individual histories to create meaningful legacies.

The following excerpt is offered for you.

Chapter Four

It was worse than anything I had ever seen, could make up, or been part of, and without question, it was awful.

The cacophony of noise from the constant blaring and honking of horns, the grumbling clamor of internal combustion engines, and the reek of fumes from the exhausts of hundreds of motor vehicles was foul and unpleasant as the roadway before me collapsed into a single lane squeezed together, bordered by a phalanx of orange cones.

I was ensnared in a relentless cycle of stop-and-go traffic, with no escape route or destination other than the one ahead.

It called to mind a colony of ants, returning to their nest, queued up, end-to-end with faceless, nameless creatures crawling before me as shimmering reflections, glaring hot off the windshields that encircle me, draw attention to the piles of rubbish, not unlike scat churned out from a procession of mechanical beetles, scattered indiscriminately alongside the cracked and uneven pavement below.

The congestion was massive, as cars and trucks of every shape and size kept coming and coming, seemingly from every direction, entrance, and on-ramp, adding to the pent-up bottleneck without pausing in their efforts to enter the impasse and onslaught of uninterrupted traffic.

It was September 1999, and I had just arrived at Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts, had picked up my rental car, and was on my way to the 33rd Ryder Cup Matches when I got trapped in traffic.

I was traveling on assignment for The Rocky Mountain Golf Radio Network, covering the biannual competitions held on the storied links of the Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, a tony, fashionable, and well-heeled suburb southwest of Boston.

The “Battle of Brookline” would be contested at the Country Club of Brookline between Team Europe, captained by Mark James, and Team United States, captained by Ben Crenshaw.

The “Battle of Brookline” would be contested at the Country Club of Brookline between Team Europe, captained by Mark James, and Team United States, captained by Ben Crenshaw.

The Country Club, one of the oldest private clubs in the United States and a founding member of the United States Golf Association in 1894, is steeped in old-school rituals and tradition and would prove a worthy test for the best international players in the world.

Getting there, however, was proving problematic.

The streets of Boston and the jumble of roads connecting Boston Harbor, the Shipyards, the Waterfront, and the City of Boston, one of the most populous capitals in New England, were pieced together long before automobiles were conceived and built.

The City itself was one of the first colonies in New England, founded in 1620 by English Puritans seeking religious freedom.

Boston is also considered the birthplace of the American Revolution and National Experience.

Nevertheless, as the town grew and expanded outward from the coast, harbor area, and marketplaces, migrating towards the city center, road traffic became extremely congested with wagons, horses, handcarts, and later motor vehicles as the Industrial Revolution commenced.

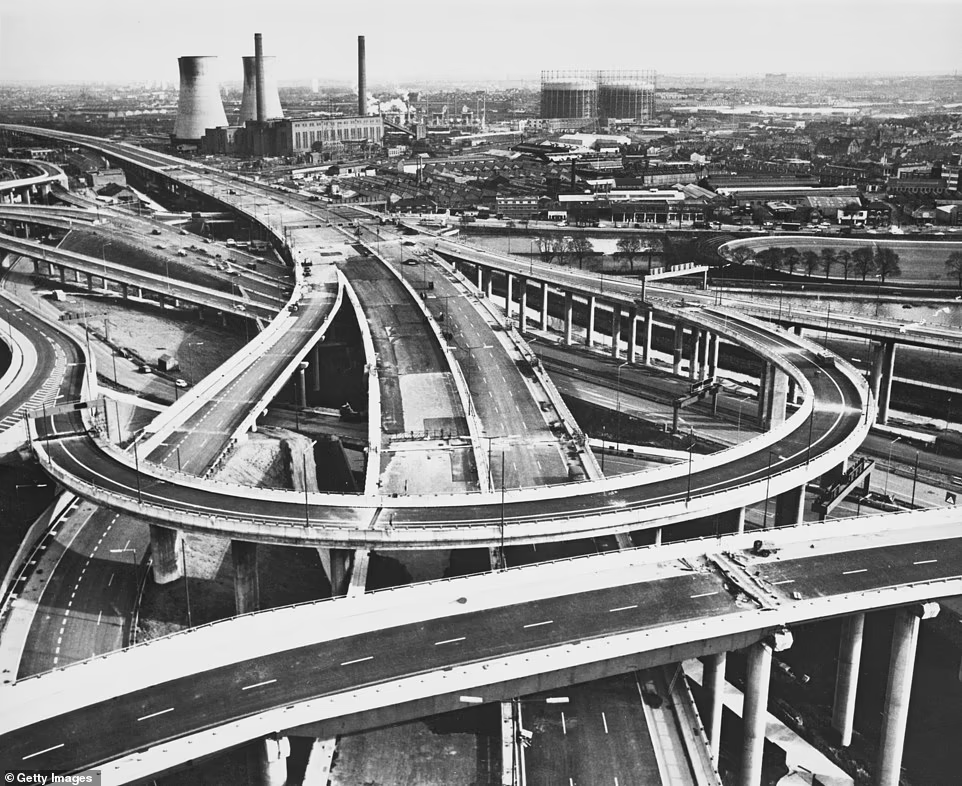

Central Artery Ring Road was conceived and constructed in 1951 before strict federal highway regulations were developed and implemented during the Eisenhower Administration.

The road would connect the coastal areas, the expanding and increasingly engaged Logan Airport, and downtown Boston proper.

However, from the start, the Ring Road was besieged with problems.

The roadway was a disaster, with tight curves, excessive entries and exits, narrow access ramps without acceleration lanes, and ever-increasing automobile traffic.

When it opened in 1959, the road carried 75,000 vehicles a day; in the early 1990s, more than 200,000 traveled regularly, making it among the most congested highways in North America.

Traffic crawled back and forth for more than ten hours daily, and the accident rate was horrendous.

Wasted fuel, time constraints, altercations, and late deliveries all compounded the problem.

The Massachusetts Turnpike Authority proposed new construction on a reworked Central Artery/Tunnel Project to relieve the congestion.

The Central Artery design, AKA, (The Big Dig) became one the biggest, most challenging highway projects in the history of the United States, comparable to the grand projects of the last century, not unlike The Panama Canal, the English Channel Tunnel, and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

The design took thirty-five years to complete but reduced traffic and improved mobility in one of America’s oldest, most congested major cities.

It also contributed to Massachusetts and New England’s economic growth while improving the environment for the entire region.

Unfortunately for me, the construction was ongoing and in progress, while I was stuck in the middle of it all, with my timeline for the day rapidly fading.

I planned to check in to the media Hotel, pick up my press credentials and parking pass, sightsee around Boston for a while, and then hit the road for the second segment of my visit.

I had purposely arrived in town a few days before the tournament to visit the New England coast, delve into my personal history, and explore the celebrated City that had contributed so much to our nation’s storyline.

My schedule was shot to pieces, so after checking in to the media hotel, dropping off my broadcasting gear, and unpacking, I quickly reclaimed my rental car and headed back out on the road, traveling south on I-495, away from the City, hoping to uncover my past.

****

I was born to goodly parents on Saturday, September 8, 1945, at 11:45 a.m. in Morton Hospital on Lakeview Avenue in Taunton, Massachusetts.

Taunton, one of the oldest and most time-worn communities in the United States, is usually a sleepy little hamlet located in the southeast part of the State, adjacent to the town of Plymouth, neighboring Cape Cod, and the iconic and scenic Martha’s Vineyard.

One of the oddities that have occurred throughout my life is I have had to answer the question of why I was born on the East Coast of America curiously so, when you consider the fact that I am the descendant of Mormon pioneers and have lived, except for university and military service, the entirety of my life in Utah.

Massachusetts, to most Westerners, seems like a foreign country.

I do not know why this subject has come up as much as it has during my life, and expecting the reaction, I have been a little too sensitive and defensive about always having to explain the reason.

The question concerns the fact that many people have open-ended conversations with others.

“Where are you from?”

“Where were you born”

I would always engage in an extended dialogue about the why and the how.

Anticipating the question, I often hesitated and said I was born in Utah, which avoided the inquiry.

The answer, on reflection, is quite simple and exciting when considering the times.

I was born a classic baby boomer, grew up a child of the fifties and sixties, and am the offspring of parents and grandparents who, as members of the Greatest Generation, endured world wars, depressions, difficult times, and the worst of the human experience the modern world had ever seen, including my parents and the world they thrust me into.

It was during this chaotic period of world history that my father, Morice Ned Waters, was a soldier in the United States Army awaiting overseas shipment to the European Theater during the last days of World War II and assigned to Camp Myles Standish, named after the first military Commander of the Continental Army and one of the original immigrants to America who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620.

Established in 1942, the War Department created the military installation in Taunton, Massachusetts, on the eastern seaboard of the United States, as a staging area for overseas replacements and as a prisoner-of-war facility for German soldiers captured during the war.

When German forces surrendered to the Allies in May 1945, effectively ending the war in Europe, my mother, Katherine Goodliffe Waters, pregnant with me and nursing my older brother Jerry, relocated from Utah to Oakridge, Tennessee, to be with her mother, Leah Goodliffe, her stepfather Weldon Peterson, along with her younger sisters, Glenna, Iris, Shirley, and Marilyn, and to be somewhat closer to my father, then stationed in Taunton, awaiting orders.

My grandfather, a structural engineer, was assigned to the Clinton Engineering Works, a sub-division of the Manhattan Project, the ultra-secret atom bomb project.

American scientists were frantically trying to complete the project before opposing forces could build their atomic bomb.

With this in mind and anticipating the war’s end, my mother, with unstoppable independence and self-determination, just twenty-three years old and five months pregnant, packed up my brother Jerry and left Tennessee.

She took the train to Taunton, unaccompanied in wartime, traveling alone, leaving behind her mother, sisters, and support group.

When I arrived in this uncertain and tumultuous world, she reunited with my father, and we were together as a family.

With the fighting in Europe over, coupled with the unconditional surrender of German forces, President Harry Truman turned his attention to the Pacific and, in August 1945, dropped the atomic bombs on Japan, which effectively ended American involvement in World War II.

Thirty days later, I was born, and Taunton, Massachusetts, became my birth city and the everlasting notation on all my official records.

Two months later, and with a stoutness derived from their pioneer heritage, my parents loaded my brother Jerry and me, bundled up against the harsh winter cold, into a 1938 Chevy held together with baling wire and tape.

In the deepest winter months of 1946, with prayers to the heavens above, set forth across the United States on two-lane, snow-covered roads bound for Utah.

With little or no lament, our family left Massachusetts and the East Coat of the Continental United States behind, bound for my grandparents’ home in Mount Aire, Utah, a housing suburb in Millcreek, Salt Lake County, where we could stay and live out the remainder of the war.

With little or no lament, our family left Massachusetts and the East Coat of the Continental United States behind, bound for my grandparents’ home in Mount Aire, Utah, a housing suburb in Millcreek, Salt Lake County, where we could stay and live out the remainder of the war.

As the three of us settled in with my grandparents, my father left us behind once again.

He continued his journey alone to Fort Lewis, Washington, to be released from serving the remainder of his tour of duty while we patiently awaited his return.

Meanwhile, the circumstances surrounding my birth and my brief sojourn to Massachusetts had profound and lasting effects on my psyche, which would linger with waning recollections for the remainder of my life, the whereabouts I would often revisit emotionally, mentally, and subconsciously.

However, the opportunity to visit those recollections physically would have to wait for another fifty years.